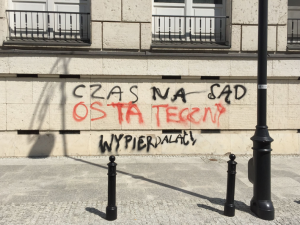

Photo: Protesters in front of the Supreme Court, July 4, 2017, Warsaw (credit Hanna Szulczewska)

In the third book of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, we find the historian’s account of the effects of an unbridled pursuit of power and the subsequent lawlessness on Athenian society: “When men are retaliating upon others, they are reckless of the future, and do not hesitate to annul those common laws of humanity to which every individual trusts for his own hope of deliverance should he ever be overtaken by calamity; they forget that in their own hour of need they will look for them in vain.”

This summer Thucydides’ warnings returned with all their urgency: on July 4, 2018, Poland’s Act on the Supreme Court, which resulted in the dismissal of nearly 40 percent of its judges, came into force amid widespread protests, including outspoken opposition by the court’s President, Małgorzata Gersdorf. The Act is the latest step in the Law and Justice party’s extensive judicial overhaul (the Act on the Supreme Court has ominously been called by protestors “the final judgment”).

Despite the European Commission’s triggering in December 2017, for the first time in its history, its sanctioning Article 7(1) of the Treaty on European Union,[1] (and as with its engagement with Hungary during Viktor Orbán’s first term, 2010–2014), a lack of adequate means and insufficient pressure has allowed the Polish constitutional and judicial crisis to unfold at an unprecedented pace. In its first year in office, Law and Justice passed 60 percent more laws than its predecessor.[2] And while the capture of Hungary’s institutions was carried out (due to Fidesz’s constitutional majority) within the letter, if not the spirit, of the law, this has not been the case in Poland. These critical legislative developments therefore not only reflect patterns seen in other autocratically leaning states, but have grave implications for the future legality of Europe.

1.

To return to the beginning: in October 2015, after eight years of leadership under the centrist Civic Platform party (PO) the conservative Law and Justice party (PiS) led by Jarosław Kaczyński, was elected on a populist and anti-immigrant platform with a parliamentary majority—the first time this had occurred in Poland since 1989. The first chapter in the current crisis was triggered when, leading up to the 2015 elections, the tenures of five Constitutional Tribunal judges (equivalent to the US Supreme Court) were set to expire in the last weeks of Civic Platform’s term in office and at the start of the new PiS government’s mandate. Before leaving office, the outgoing Civic Platform government passed the Act on the Constitutional Tribunal, which included an article to appoint five candidates to these posts.

On December 3, 2015, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled that three of the five vacant seats had been legally filled, as those judges’ terms of office had ended within the incumbent government’s mandate. This judgment was recognized as valid by international bodies such as the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission.[3] Anticipating this judgment, however, on December 2, the day before the Tribunal’s ruling, the Law and Justice government—based on an amendment not yet entered into force[4]—rapidly passed resolutions deemed without legal basis,[5] and elected five judges of its own, the majority of whom were sworn in by Poland’s president at 1:30 a.m. on December 3.[6]

This sequence of events set in motion Poland’s constitutional crisis, characterized by a pitched battle between the Law and Justice–dominated parliament on the one hand, and the country’s Constitutional Tribunal on the other. President Andrzej Duda refused to take the oath from the three judges the Tribunal considered validly elected; the government also refused to publish other selected key rulings by the Constitutional Tribunal.[7] Not only did the government fail to accept the judgments of its country’s highest authority, but the Tribunal was left crippled by the three unresolved vacant seats, as well as by other disputed procedural changes.[8]

In response to the Constitutional crisis, on January 13, 2016, the European Commission decided to evaluate the Polish situation under its Rule of Law Framework, a multi-step process that includes dialogue, a written opinion, and a sequence of “Recommendations” designed to address concerns regarding a serious risk of constitutional breaches. Despite this, during the first quarter of 2016, Law and Justice continued to pass other controversial laws, including a Civil Service Act,[9] which removed over 1,500 state employees and eliminated the requirement that candidates for senior civil service posts be apolitical for five years before nomination; a series ofsurveillance acts,[10] which give Polish law enforcement authorities extensive access to electronic communications with limited judicial oversight; an Amended Public Assemblies Act, which restricts the right to free assembly,[11] and a package of public media acts that ended the mandates of Poland’s public television and radio managers[12] and established, as in Hungary, a National Media Council that places public media under the control of the government.[13]

Lesser known, but equally significant for civil society, is the “Act on the National Freedom Institute,” which places access to public funding for civil society organizations—including EU funds—under government control, reminiscent of Russian and Hungarian NGO laws.[14] Most visible in the international press was the passing of the controversial “Holocaust Act,”[15] reviving a former 2008 law,[16] which legally forbade public use by Polish nationals and foreigners of the term “Polish death camps” and assertions of co-responsibility by the Polish Nation for Nazi crimes (though potential jail sentences were revoked under international pressure in summer 2018).

During this period public discourse concerning the fundamental role of the Constitutional Tribunal began to collapse. In early spring 2016, the Deputy Minister of Justice stated, before a particularly sensitive ruling on March 9, that the next day’s proceedings would “not be a hearing of the Constitutional Tribunal, but a gathering of people who sit in the Tribunal at best.” This opinion, reported with concern in the press, was not repudiated by the government, but repeated by the Minister of Justice.[17]

2.

Although the European Commission concluded in July 2016 that there was a “systemic threat to the rule of law in Poland,”[18] the Constitutional crisis did not abate.[19] The Tribunal remained under intensive pressure to accept PiS’s “midnight” nominees to the Tribunal, a tactic resisted by the Tribunal’s president Andrzej Rzepliński. Here, the details are crucial: just prior to Christmas 2016, as Rzepliński’s term was set to expire, Law and Justice passed a new interconnected package of laws[20] whose goal was to circumvent further obstructions and obtain a majority on the Constitutional Tribunal.

The centerpiece of these laws was the creation of a new position—which does not appear in the Polish constitution—that of “Acting President of the Constitutional Tribunal,”[21] a step immediately singled out by the European Commission for its threat to the rule of law.[22] With Rzepliński’s retirement, Law and Justice was also concerned that the Tribunal’s vice-president, Stanisław Biernat, would have continued to resist PiS’s initiatives. With the swiftness of a perfectly executed pas-de-deux, on December 19, the day Rzepliński’s term ended, President Duda named a Law and Justice–appointed judge, Julia Przyłębska, to this newly created position.

On December 20, Przyłębska, in her role as acting President, officially admitted the three judges without valid basis to the Tribunal. On the same day Przyłębska convened a meeting to nominate the Tribunal’s president, despite a request by eight judges for it to be postponed. The three new judges and three other PiS loyalist judges put forward Przyłębska (and one other nominee) for the position of President of the Constitutional Tribunal; all other judges abstained. The next day, President Duda swore in Przyłębska as the Tribunal’s President.Przyłębska then informed Tribunal Vice President Stanisław Biernat that he was obligated to use his remaining leave until the end of his mandate.

3.

In what has become one of PiS’s trademarks, the party had hoped that the installation of the Tribunal’s new President during the Christmas holidays would shield it from public criticism. However, this highly controversial procedure led the European Commission, on December 21, 2016, to issue its second Framework Recommendation, which stated that the procedure and appointment of the Tribunal’s new president was “fundamentally flawed as regards the rule of law… and seriously threaten the legitimacy of the Constitutional Tribunal.”[23]

Now in possession of the Tribunal, in mid-July 2017 the government swiftly pushed three new bills through the Sejm and Senate, which were presented to President Duda for his signature. They included the Act on the Supreme Court, which oversees the country’s lower courts; the Act on the National Council for the Judiciary (NCJ), an institution that, among its other responsibilities, appoints the country’s judges and oversees the validity of elections; and the Act on the Organization of the Ordinary Courts,[24] which allows for the dismissal and appointment of their presidents by the Minister of Justice.

When the contents of the bills were made public, the country was again plunged into civil turmoil. In its initial form, the Act on the Supreme Court would have mandated the immediate retirement of all of its judges. While awaiting the president’s decision, thousands gathered each night in Warsaw before the Supreme Court, then marched along the capital’s main boulevard to the Constitutional Tribunal and Sejm. Faced with mounting civic resistance and internal party divisions, President Duda declined to sign the bills, but announced they would be revised and resubmitted to the Sejm after its summer recess. In late July the Commission issued its third and final Recommendation, stating that a “constitutional review of these laws is no longer possible” and that the “independence and legitimacy of the Constitutional Tribunal are seriously undermined and, consequently, the constitutionality of Polish laws can no longer be effectively guaranteed.”[25]

The contents of President Duda’s revised bills, which were unveiled in November 2017, remained, however, essentially the same, with the exception that nearly 40 percent of the Supreme Court judges (those over sixty-five), rather than the whole Court, would be forced into mandatory retirement. The revised Act on the Supreme Court also contains the provision that Poland’s president can personally determine which of the retired judges are allowed to prolong their tenures after the age of sixty-five, further politicizing the method of selection. The Act also introduces a new disciplinary chamber within the court itself, whose members are elected by parliament, effectively creating a political arm of the government within the judicial body. In Law and Justice’s “White Paper on the Reform of the Judiciary”—its response to the European Commission—the Act on the Supreme Court is principally justified by the claim there remain former communists within the judiciary, never held to account, who wrongly sentenced oppositionists during Martial Law.[26]

This has been disproved by Iustitia, Poland’s association of judges, citing the fact that in 1990 81 percent of the Supreme Court’s judges were replaced. Those adjudicating 1981–1983 in lower instances and later promoted to the Court represent six out of ninety-three positions. Thus, according to Iustitia, the Act on the Supreme Court is not only a “completely disproportionate measure,” but also not in compliance with case law of the European Court of Human Rights, where the “mere unverified conclusion that unspecified judges are unworthy to adjudicate cannot constitute grounds for shortening their terms”[27] and any dismissal requires criminal or disciplinary appraisal.

4.

The Polish government and the European Commission headed towards a final showdown over the course of ten tense weeks in late fall 2017, after the unveiling of the President’s revised Act on the Supreme Court, which, in the opinion of the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe, enables “the legislative and executive powers to interfere in a severe and extensive manner” and thereby poses “a grave threat to…the rule of law.”[28]

On December 20, 2017, President Duda signed the revised Act on the Supreme Court. The same day the European Commission issued a “Reasoned Proposal” and announced its decision to trigger Article 7 (1) of the TEU.[29] Regarding this final step, the Commission stated: “Judicial reforms in Poland mean that the country’s judiciary is now under the political control of the ruling majority. In the absence of judicial independence, serious questions are raised about the effective application of EU law, from the protection of investments to the mutual recognition of decisions in areas as diverse as child custody disputes or the execution of European Arrest Warrants.”[30][31] Earlier, in November, in response to a resolution passed in the European Parliament with a view to holding a plenary voteon Article 7(1),[32] portraits of the six participating MEPs from the Polish opposition party Civic Platform were hung on mock gallows in Katowice.

5.

While signed into law by President Duda in December 2017, the Act on the Supreme Court did not go into effect until July 4, 2018. Despite civic fatigue and growing despondency, protesters once again took to the streets, in particular in support of Supreme Court President Małgorzata Gersdorf, who issued a public statement citing the inviolability of her six-year term, which is enshrined in the Polish Constitution, and her determination to contest being forcibly removed from her post. The morning after the Act went into effect, Gersdorf made her way with difficulty through the streets towards the Court, and finally succeeded in entering the building, protected by a chain of protestors.

The image of the Supreme Court’s President being barred from entering the Supreme Court to fulfill her professional functions created a temporary public relations—as well as constitutional—problem for Law and Justice. However, on July 26, Law and Justice simply passed a new law that alters the conditions for the election of the President of the Supreme Court.

But here it is not only the Supreme Court that is at stake: the President of the Supreme Court—already one of the Poland’s key judicial posts—also automatically serves as the President of the Court of State, which rules on questions of infringement of the constitution by Poland’s President or members of parliament—a position that PiS now appears increasingly anxious to secure.

The tragedy of Poland’s constitutional crisis has far-reaching implications for all of Europe. As the Commission stated in its decision to trigger Article 7(1), the breakdown of rule of law in Poland places Europe’s interdependent legal system in question. In a recent landmark ruling Minister for Justice and Equality v. LM (The “Celmer Case”),[33] the European Court of Justice ruled that an Irish court could refrain from extraditing a Polish national where there is a risk that the individual would “suffer a breach of his fundamental right to an independent tribunal.” In Justice Aileen Donnelly’s assessment, the European Commission’s Reasoned Proposal “sets out in stark terms what appears to be the deliberate, calculated and provocative legislative dismantling” of the independence of Poland’s judiciary.”[34]

While this decision is an important step, the ECJ ruling still falls short: in such a case, before mutual trust and European arrest warrant procedures could be permanently suspended, the TEU’s sanctioning mechanism Article 7(3) would have to be adopted.[35] This prospect is unlikely in Poland’s case, due to Hungary’s veto power on the Council. As Kim Lane Scheppele has suggested, the ECJ ruling therefore has dangerous implications for European rule of law as it implies that “a breach of a Member State’s obligation to honor European values isn’t an assessment that the European Commission—or even the ECJ—can make.”[36] With 2019 European Parliament elections approaching, Europe faces the danger that illiberal democracies might attempt to alter the European constitutional order with the potential to harm the legitimacy of the interdependent European legal system.

Neither internal nor external pressure have thus been able to diminish the scope of Law and Justice’s ambitions, set on the same track of populism, nationalism and isolationism as Hungary, Turkey and Russia. This summer President Duda even suggested further testing Poland’s fundamental commitment to Europe with a fifteen-point referendum, which includes the question: “Are you for the inclusion in the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of guarantees of Poland’s sovereignty within the European Union and the priority of the Constitution over international and European law?”[37] For the first time in thirty years, Poland faces exclusion—whether chosen or through sanctions—from Europe, and subsequently a position beyond the oversight of European rule of law.

Poland, as one of the most prosperous and previously most democratically-oriented countries of the former East Bloc, is also one of the most complex cases when it comes to the recent rise in autocratic populism. The country has experienced continual economic growth since 1989, was almost alone in the EU to weather the 2009 economic downturn, and is enjoying its longest period of contemporary sovereignty. Although during the first years following the democratic transition it was common in the East to speak of an “economy of patience,” where populations accepted hardships due to the perceived importance of civil liberties, it has now become evident that economic incentives stand almost alone, and those same liberties are freely exchanged for a growing system of clientelism, previously largely absent in Poland.

Standing outside the Sejm in Warsaw in July 2018, now permanently protected by metal barriers, one indeed fears for those “common laws of humanity to which every individual trusts for his own hope of deliverance should he ever be overtaken by calamity” that Thucydides evokes. Unless Europe acts quickly, it will not only be Poland, but all of Europe that “will look for them in vain.” Law and Justice’s recklessness and the EU’s lack of firm resolve regarding the values set out in the TEU augur dark things to come.

The author thanks Dr. Adam Krzywoń for his comments on this essay.

℘

[1] On January 13, 2016, the European Commission decided to evaluate the Polish Constitutional situation under its Rule of Law Framework—if the Framework establishes that there is “a clear risk of a serious breach by a Member State” the preventive procedure Article 7(1) of the TEU can be activated. In the case of a “serious and persistent breach by a Member State” sanctioning mechanisms Articles 7(2) and 7(3) may result in the suspension of certain rights “including the voting rights of the representative of the government of that Member State in the Council.” See: Consolidated Version of The Treaty On European Union: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:12012M007 [2] For statistics (2011–2015): http://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm7.nsf/page.xsp/prace_sejmu (2015–2018) and (http://www.sejm.gov.pl/Sejm8.nsf/page.xsp/prace_sejmu). [3] “Opinion on Amendments to the Act of 25 June 2015 on the Constitutional Tribunal and Poland,” adopted by the Venice Commission at its 106th Plenary Session (Venice, 11-12 March 2016). Accessible at: http://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2016)001-e [4] Act of November 19, 2015, Amending the Act on the Constitutional Tribunal was to enter into force on December 5, 2015. [5] See: “The Constitutional Crisis in Poland 2015 –2016”, p. 22, accessible at: http://www.hfhr.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/HFHR_The-constitutional-crisis-in-Poland-2015-2016.pdf [6] Four judges were sworn in on December 3, 2015, and the final judge on December 9, 2015. [7] Certain rulings of the CT were later published, but only after the government deemed them to be superseded by subsequent legislation. For a detailed description of legislation see: “Reasoned Proposal In Accordance With Article 7(1),” op. cit. [8] Changes introduced by the Second Act Amending the Act on the Constitutional Tribunal, signed into law on December 28, 2015, included the stipulation that the Tribunal hear cases as a full bench (of 13 out of 15 judges) and in the sequence in which they were filed and that disciplinary proceedings could be initiated by the President and Minister of Justice against a Tribunal judge. See: “Opinion on Amendments to the Act of 25 June 2015,” op. cit. [9] Act of December 30, 2015 Amending the Civil Service Act. [10] These included: Act of January 15, 2016, Amending the Police Act and certain other acts; Act of March 11, 2016, Amending the Criminal Procedure Code and certain other acts; Act of June 10, 2016, on Counterterrorism. [11] Act of December 13, 2016, Amending the Peaceful Assembly Act. [12] Act of January 7, 2016, Amending the Act on Radio and Television (the “Small Media Act,” “Mała Ustawa Medialna“). [13] Act of June 22, 2016, on the National Media Council. [14] September 15, 2017, Act on the National Freedom Institute—Centre for the Development of Civil Society Centre for the Development of Civil Society of Poland. [15] Act of January 26, 2018, amending the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance. [16] Polish Criminal Code, Article 132a. [17] “The Constitutional Crisis in Poland,” op. cit.,p. 32. [18] Commission Recommendation (EU) 2016/1374 of July 27, 2016, regarding the rule of law in Poland. Accessible at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016H1374 [19] In response to the July 27 Recommendation, the Polish government “disagreed on all points with the position expressed in recommendation and did not announce Andy new measures to alleviate the rule of law concerns.” See: “Reasoned Proposal in Accordance with Article 7(1) of the Treaty on European Union Regarding the Rule of law in Poland,” p. 6. Accessible at ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/document.cfm?action=display&doc_id=49108 [20] The Act of November 30, 2016, on the Legal Status of Judges of the Constitutional Tribunal; The Act of November 30, 2016, on the Organization of and Proceedings before the Constitutional Tribunal; The Act of December 13, 2016, implementing the Act on the Organization of and Proceedings before the Constitutional Tribunal and the Act on the Legal Status of Judges (the “Implementing Act”) were published in Official Journal of Law (Dziennik Ustaw) on December 19, 2016, the day of Rzepliński’s retirement. [21] As defined in the Implementing Act and the Act on the Legal Status of Judges. [22] Commission Recommendation (EU) 2017/146 of December 21, 2016, regarding the rule of law in Poland complementary to Recommendation (EU) 2016/1374, accessible at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2017.022.01.0065.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2017:022:TOC [23] Commission Recommendation (EU) 2017/146 of 21 December 2016, ibid. [24] President Duda signed the Act on the Organization of the Ordinary Courts on July 25, 2017. [25] Commission Recommendation (EU) 2017/1520 of July 26, 2017, regarding the rule of law in Poland complementary to Recommendations (EU) 2016/1374 and (EU) 2017/146. [26] “White Paper on the Reform of the Judiciary.” Accessible at: https://www.premier.gov.pl/files/files/white_paper_en_full.pdf [27] “Response to the White Paper Compendium of the Reforms of the Polish Justice System, Presented by the Government of the Republic of Poland to the European Commission,” p 3. Accessible at: http://www.statewatch.org/news/2018/mar/pl-judges-association-response-judiciary-reform-3-18.pdf [28] “Opinion on the Draft act Amending the Act on the National Council of the Judiciary, on the Draft Act Amending the Act on the Supreme Court, Proposed by the President of Poland, and on the Act on the Organization of Ordinary Courts (8-9 December 2017),” p. 26. Accessible at: http://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2017)031-e. [29] “Reasoned Proposal in Accordance with Article 7(1),” op. cit. [30] “Rule of Law: European Commission Acts to Defend Judicial Independence in Poland.” Accessible at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-5367_en.htm [31] The Commission also issued a fourth and complementary Recommendation: “Commission Recommendation of 20.12.2017 regarding the rule of law in Poland complementary to Commission Recommendations (EU) 2016/1374, (EU) 2017/146 and (EU) 2017/1520.” Accessible at: ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/document.cfm?action=display&doc_id=49107 [32] This was held on November 15, 2017: “European Parliament Resolution on the Situation of the Rule of Law and Democracy in Poland.” Accessible at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=MOTION&reference=B8-2017-0595&language=EN [33] Case C-216/18 PPU, Minister for Justice and Equality v LM (Deficiencies in the system of justice). Press release accessible at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-07/cp180113en.pdf [34] The Minister for Justice and Equality v. Celmer. Accessible at: http://www.europeanrights.eu/public/sentenze/Irlanda-High_Court-23marzo2018_Request_for_Preliminary_Ruling.pdf [35] Case C-216/18 PPU, see paragraphs 71–72: http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf;jsessionid=9ea7d2dc30d849bb0e5ed78a4e3494f285da9d2d6ecd.e34KaxiLc3qMb40Rch0SaxyPaxn0?text=&docid=204384&pageIndex=0&doclang=en&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=260913 [36] Kim Lane Scheppele, “Rule of Law Retail and Rule of Law Wholesale: The ECJ’s (Alarming) “Celmer” Decision,” accessible at: https://verfassungsblog.de/rule-of-law-retail-and-rule-of-law-wholesale-the-ecjs-alarming-celmer-decision/ [37] Rejected by Polish Senate on July 25, 2018. See: http://www.president.pl/en/news/art,778,the-proposed-constitutional-referendum-questions.html Subscribe to Read More