for M. S., lively in tempo, brilliant in style

Today I decided to write a poem for you, knowing today is really many days and youare a singular plenitude.

Of course every poem is a way of talking to the dead or to the dying—which is to say everyone—so this poem is for everyone, as much as it is for you, Maureen, my sweet friend, Maureen Seaton.

When I type your full name, I hear it: More sea. More to see and a vast ocean in which to swim. For a time, we both lived so close to the spume our heads were frothy as lattes some days, our freckles aglint with salt.

When I die, I might like to join the coral reefs. When you died, you joined the trees.

[insert fleuron here—it feels like there should be a fleuron]

Of course every poem is a way of teaching us something we might not know or something we might forget.

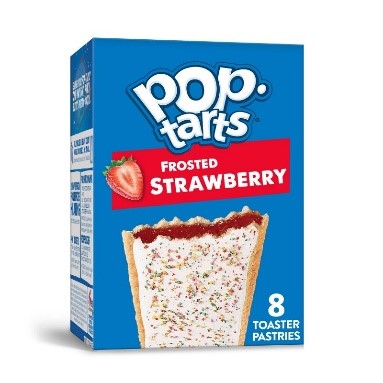

For instance, on the Kellogg’s Pop-Tart box, did you know it’s not a hyphen that separates the words but an interpunct, that big dot floating like the moon between a series of letter-stars?

Of course the moon is an interpunct.

Of course the moon is the fleuron we’re always hungry for.

•

I have so many questions, Maureen, many of them about poems. Like why did William Carlos Williams call it “A Sort of a Song” when it was precisely a song? (Saxifrage, his fleuron.)

In Florida, ixora is my flower that splits the rocks.

WCW was right, of course, about ideas. A poem should be full of real things, and imaginary things, but most importantly, things.

Some things a poem might include: Lava lamps. Lollipops. Stationary bikes with those big, water-filled wheels. (Are they retro now—as hard to find as a modern-day waterbed?) Outside bikes with baskets and banana seats and streamers flying from the handlebars. (I’m getting the sense that I may be retro, too.)

Not only things, but people, places, a parade of concrete nouns. That’s how your poems are/ were/ are.

Present tense gets tricky, doesn’t it, after someone we love is gone.

Are you ever jealous of your poems, Maureen, of the way they get to live beyond you? And would I trade them, all your poems in a bonfire at the beach, all your words burning, burning, to have you back? Would it even be you who returned to us, or would you go up with the smoke, down with the ash, become another version of yourself?

I’ve never been clear about bodies—where they end or how. So why should it be any different with the bodies of work we bear?

•

Of course every poem is a story, even if it isn’t a narrative. And every poem is an instance of truth, even the fictional ones. (Nota bene: This isn’t a fictional one.)

Once upon a time I lived on a barrier island between two poets who were best friends. I didn’t feel like an interloper. They didn’t let me. You didn’t let me, either of you. (The you, too, is a plenitude.) No, I felt lucky as a golden taxi on the Intracoastal Waterway. Even more than lucky—I felt ensconcedin brilliance and style.

Last July I picked up our friend Denise from the airport, and she told me your time was coming faster than we thought. She reached for the word hospice—a soft word, a swaddling of sound, gauzy as the gauze they use in wound care—and isn’t death a wound? And though I couldn’t hear it, I could see the spice in it and hope your hospice was cinnamon-filled, that you made a joke about sin to the nurses, that there were always some cloves mixed in.

Tonight, in January, I’m picking up our friend Denise from the airport again. Why do I keep wishing she’ll reverse the spell, that she’ll tell me you’ve reemerged six months later, healthy and whole? (Six months: even hospice has a deadline, I learned [insert relevant pun], an estimate for the time it takes to die.) Instead, you’ll live on past your deadline, your expiration date expired, harmonizing with Ella Fitzgerald: “Let’s call the whole thing off!”

•

Of course every poem is a meditation on language, the way words come to mean—by which I mean the way words fail us and the way we fail words.

Wow, that got heavy, right? I like how the word heavy actually feels heavy, a bag of stones, and how the word light actually feels light—and bright at the same time. Like a sequin.

Lite•Brite is another thing a poem might include. Its motto: Create art with light.

That’s what you did, Maureen. That’s what you always did.

Sequins, your final poems.

•

Of course every poem is an aha! moment, which I think of more specifically as a wow moment. Every poem has its own wow factor, showing the poet, not just the reader, what they need to know or what they may have forgotten.

I love to say wow for several reasons:

1) It’s an interjection, the most whimsical part of speech. (I know you’ll agree.)

2) It’s a palindrome, the way I wish my own name were. (Lucky Annas! Lucky Hannahs!)

3) It can join up with other words, like bow and pow, to build rhyming teeter-totters on the playground of our speech.

I’m less fond of the way wow becomes mom when you turn it upside down.

But this poem isn’t about moms—not the mom you are/ were/ are, not the mom I’m not/don’t want to be/will never be—or even about my own mom really . . . though she does creep in. She has a way of seeping through.

Let’s call this poem mother-adjacent, which it turns out most poems are.

My mother had a double mastectomy while I was getting my PhD. In the dream I said, to no one in particular, “It’s okay. I wasn’t breastfed. Her body never really belonged to me.” (Does anyone’s body ever really belong to us?)

In waking life, I ordered veggie lo mein and half a dozen spring rolls, then backed into a parked car on my way to Double Dragon. I could blame black ice, but it wasn’t.

Coincidence? Preoccupation? My mother rattling me from under anesthesia and seventeen states away?

“It’s okay,” I told the vehicle’s owner. “I have insurance.”

A few months later, I intervened before she could kill herself—my neighbor, not my mother. Put another way: first, I ruined her car; then, I ruined her suicide.

My mother, with no help from me, survived.

•

One day I meant to type prepositions into a document but typed premonitions instead.

This was back in that limbo—between your hospice and your death—but perhaps I had glimpsed already a world without you, Maureen, and could not imagine living by or near that world.

Yet here I am, prepositioning, on a different today that will become a perpetual tomorrow. Somehow I find myself living ina world that now swirls on without you.

•

Of course every poem is an elegy. Every single mother- (God, she’s everywhere!) fucking poem.

•

Sometimes the poem is speeding ahead of me like a car on a country road—a car that knows where it’s going, where a break in kudzu gives way to a whole secret road.

Angie, my wife, grew up on roads like these. She isn’t afraid to drive them. She always knows where the kudzu breaks.

You met my wife, Maureen, and I met yours. Many times. I never dreamed I’d grow into a life where this was possible. Women with wives. Women who were friends with women with wives.

I hate the word wife except that it rhymes with life, and that’s what Angie has given me. More life in my life—like Lori gave you. More purposeful prepositions.

•

Sometimes I make the volta.

Sometimes I crash.

I pride myself on never running out of gas.

#poetrypetrol

•

Of course every poem is also a metaphor.

•

As of today, this day, I have traveled to forty-six states.

Not Iowa

Not Vermont

Not Michigan

Not Mississippi

I remember how we used to jump Double Dutch on the cracked asphalt, calling out the letters until the word became a singular plenitude (which all words, all poems, are): M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I.

In Washington State, we did this. (Did you do this in New Jersey, too?) We did this all day long.

It’s also why I wasn’t wrong when the teacher asked, “How many letters are in Mississippi?”—and I replied, “Four.”

Four letters, like actors, making multiple cameos. Everyone, including our letters, always plays multiple roles.

•

I miss so much, Maureen. Maybe that’s why I’ve missed Mississippi for so long.

•

I miss those little cups of half–peach sherbet, half–vanilla ice cream. (Do they even make them anymore?)

I miss turning a Capri-Sun upside down, stabbing the silver pouch with the yellow straw. (All my memories glowing like a Lite•Brite.)

I miss cola-flavored Slurpees on a road trip.

•

In our yard, there is always a curly-tailed lizard named Kermit doing pushups on the banyan tree.

Angie says, “In Florida, that really doesn’t count as weird.”

She’s right, of course, as per.

And now I’m thinking about the word weird and how it is weirdly hard to spell—the internalized rhyme of i before e except after c, yet the e comes before the i which follows a w. (What?)

Weird is a weird word—a rule-breaker of a word. (I like it.)

And now I’m thinking about this time in high school when we went on a camping trip with our class, and the leaders broke us up into small groups and gave us markers and posterboard, and then we spread out across the park or nature preserve—whatever it was, wherever it was—and had to choose a quote that would represent and distinguish our group from all the others.

There was a girl in my group named Colleen, who had a twin sister named Becky in another, and Colleen said, “I think our group should use a quote from Barney,” and I said, “Barney who?” and she said, “Barney the purple dinosaur,” and I said, “Isn’t that a kids’ show?” and she said, “Barney is actually really profound, and Barneysays, ‘Everyone is weird, so being weird is normal. If everyone were normal, that would be really weird.’”

Three things:

1) Poems are weird.

2) Twins are weird.

3) I do not miss high school.

•

Sometimes there’s a cardinal at our window banging his beak on the glass. He sees another cardinal. He wants to defend his nest. But it’s always himself—just himself—he’s fighting.

This is precisely what humans and cardinals have in common.

•

Tonight it’s not a cardinal but the moon tapping at the high glass, slipping under the screen door, sliding its yellow fingers between the slats.

Sometimes the moon behaves eerily like a mother.

•

I think it’s weird how refrains repeat in music and in poems, but to refrain also means to stop doing something.

So, a poem’s refrain actually refrains from refraining!

•

I miss Pacific Standard Time, when we had three more hours to do anything, everything—three more hours before we said goodbye to Christmas, three more hours after the ball dropped in Times Square to make our resolutions and bang our pots and pans.

I miss calling someone on the East Coast and asking, “What’s the future like there?” (The future, of course, is a kind of weather.)

I miss mountains, Maureen, living here in the flattest state. (I learned that on Jeopardy!) When you died, you lived at the base of a mountain. You died on Mountain Time.

•

In preschool Eric Grove taught me to bite my lip—the pleasure of ripping the skin with my teeth, that little jolt of pain followed by that stunning tang of blood.

Now it’s forty years later, and I still bite my lip when I’m nervous, when I’m sad, when I’ve lost someone I can never get back.

I try to find Eric Grove on Facebook, but it’s hopeless. He’s lost in the trees of his name.

You’re laughing already, aren’t you, Maureen? I can still hear your laugh, which makes me laugh, too, contagious as laughter is. We’re guffawing together now because I can’t see the Eric for the trees!

•

Tonight, which is just like today only darker, the moon resembles a perfect ripe banana.

Okay. I admit that’s hyperbole.

Tonight the moon resembles a perfect ripe plantain.

•

Of course all poems move by association. It’s part of their half-moon charm.

•

Once, you were married to a man, Maureen. Once, I was engaged to one. Different men, of course, and each man a singular plenitude.

Still, I couldn’t get over how weird it was—that I was going to be a bride and he was going to be a bridegroom. Right there, in the language, he was going to have both of us.

Instead of “I do,” I ended up saying, “I’m out.”

Like any poem, I was being multivalent. Like every poem, I was trying to save my life.

•

You know what else is weird—how there’s nothing casual(ever) about casualties, yet everything is (always) formal about formalities.

•

When I visited Austin, Texas, they had all these bumper stickers, Keep Austin Weird.

When I lived in Louisville, Kentucky, they had all these (obviously plagiarized) bumper stickers, Keep Louisville Weird.

When I moved to Florida, I thought, Who are these other places kidding?

•

I’m furious at cancer, Maureen—that monster that made you a casualty. I swear to God, if there’s a coat check or a valet stand or some seraph peddling soap in a fancy bathroom in the Afterlife, I will storm in there and make the biggest scene. Fuck every formality that holds our life-and-deaths at bay, keeps us busy searching for a ticket or a coin.

I don’t really believe in an Afterlife, though.

I think the best I can hope for is a chance to commingle with a coral reef, the way Julia Child did, her cremains floating off the coast of Key West.

I’m glad to know you became a tree, Maureen—a tree at the base of a mountain, growing in Forever Time.

•

Of course all poems are epistolary, at least implicitly. We’re always writing to someone, even a stranger we’ll never meet.

The anonymous poem says, Hello, it’s nice to meet you, how do you like your eggs? The poem says, I’m happy to poach you something, perhaps a line from another poem.

A poem you wrote says, The hour is holy, says Rilke, so I try to speak into the hour, but every time I press unmute a song by Ravel I love wildly startles those in charge of the hour—my children, the sea, mountains, the light that arrives in the tree unbeckoned.

A poem I wrote says, I run past Hayes Street, past the Diane Motel which you once wrote “lost all of its vowels” in a poem. Well, a hurricane you described in a poem.

You’re the you in my poem, Maureen, that singular plenitude.

It’s your line I poached this holy hour.

It’s your vowels I scoop up in my Solo cup.

Your death is the hurricane.

•

Last post on your Twitter feed: Maureen Seaton passed away peacefully on August 26, 2023. Thank you to all who loved her and continue to love her work.

I still find myself surfing for updates on who you are/were/are.

Will this keep me afloat? Will it pull me under? My friend Dana says grief is the hardest wave.

•

Think how many words there are—first that, just that.

Then, think how many words there are to mark the culmination of an enterprise.

You’ve got your afterword (pretty literal), your epilogue (kinda geeky, kinda Greeky), your coda (Italian for tail, which has a sweet swish about it), your bonus footage (heck, yes!), even your blooper reel (snort-laugh).

Not one of these is quite as nice as an interstice, but however you slice it, whatever you call it, I like when there’s more at the end.

[insert encore here—insert tree]