Photo of Ottilie Mulzet courtesy of Martin Brouk.

NER international correspondent Ellen Hinsey talks with translator Ottilie Mulzet about the Hungarian women poets Zsuzsa Beney, Ágnes Gergely, Magda Székely, Zsófia Balla, Zsuzsa Rakovszky, & Krisztina Tóth.

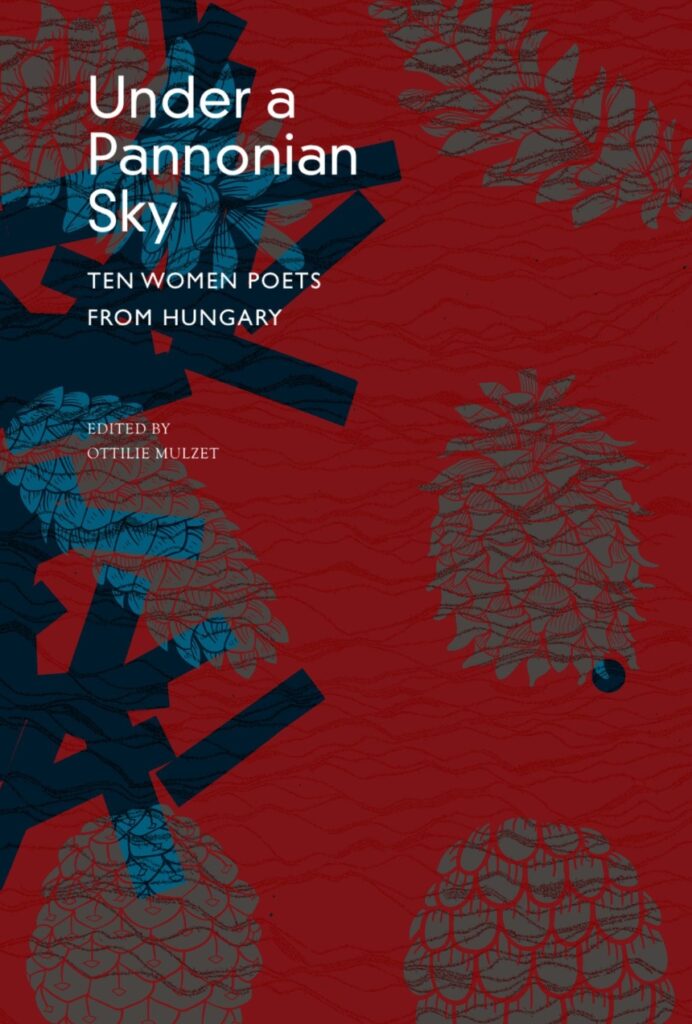

Ellen Hinsey: In this Literature and Democracy feature we have the honor of presenting six Hungarian women poets who in English translation have not received the international recognition their work greatly deserves. This selection of poems comes from the anthology Under a Pannonian Sky: Ten Women Poets from Hungary (forthcoming, December 2025) from Seagull books, for which you have served as editor and co-translator. Let’s start with how this volume came about—

Ottilie Mulzet: I’ve wanted to assemble an anthology like this for a very long time—in fact it has always been one of my dreams as a translator—but I only started working on it in earnest in 2018, during a residence at the Hungarian Translators’ House in Balatonfüred. I was enormously inspired by a book that I came across in Room No. 2—one of the most beautiful rooms in the house, with an original tiled stove in the corner and large double-glazed windows facing the front yard with its fruit trees and sculptures. The road outside, Petőfi Sándor utca, is often full of heavy traffic, but in Room No. 2 it almost seems as if you were in a different century. Here is where I feel, most strongly, the spirit of all the writers and translators who have passed through, from the days when the Lipták family maintained the house (a summer villa built in 1880) as a vital literary salon, beginning in the 1940s and up until the 1980s. Hungary’s greatest poets, such as János Pilinszky, Sándor Weöres, and Ami Károlyi, or prose writers like Tibor Déry, were regular visitors. Since 1998, the Lipták villa has functioned as a residence for translators. Unfortunately, though, at this point in time, its future funding looks uncertain.

In Room No. 2, I came across a comprehensive compendium of at least one hundred Hungarian women poets, writing from the sixteenth century up until the end of the second millennium—sadly, the only publication of its type to date. From this emerged my project to focus on a particular historical and generational cross-section of Hungarian poetry and, moreover, one with a poetic force and moral reach that would be transnational in its appeal.

EH: Your choice in this forthcoming anthology of Hungarian women poets thus includes both writers born in the 1930s—who personally witnessed the Second World War and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution—as well as those who have come of age in recent decades. In reading these poems one is immediately struck by the power with which, particularly in the case of the older poets, they address extremity and ethics with remarkable lyric strategies—

OM: Yes, this choice of the historical era in which the poets were born and created was a very deliberate strategy—the dates of their births precisely cover a half-century from 1922 to 1972. The first poet in the volume, Ágnes Nemes Nagy (translated by George Szirtes), began publishing after the Second World War. The youngest poet in the volume, the Romanian-born Anna T. Szabó (translated by herself and Claire Pollard), began publishing a few years after 1989, when the Communist regimes fell in both Hungary and Romania. Already, one can see how the lifespans of both the oldest and youngest poets in the volume were impacted by such overwhelming historical events.

All of the older poets in the volume were greatly influenced by the Újhold (New moon) literary periodical. It was published in Hungary for only two years, but remained enormously influential in the decades to come. Újhold was shut down in 1948 due to ideological reasons (the prominent Marxist critic György Lukács termed it “the ivory-tower protests of an isolated individual self”), and doors to publication were slammed shut for its writers, many of whom survived on translation and by writing children’s books for at least the next decade. Ágnes Nemes Nagy said of the poetic mission of this generation of writers:

To write about the extreme: about the assault on existence in a spiritual and physical sense. About physical misery and madness. We let these experiences crawl into our poems.[1]

I feel particularly drawn to the Újhold poems for how they confront devastating historical experiences on a deeply lyrical level that—while often not “personal” in the sense of the Western lyric tradition—they nonetheless convey an intensely individual response.

EH: Let’s speak a bit more about the impact of these poets, whose work carries the weight of history, but also what differences they bring to their poetry as women writers—

OM: Poets of East and Central Europe have often fulfilled a kind of role of “speaking for the nation in times of crisis,” from the nineteenth-century Romantics like Petőfi or Mickiewicz to twentieth-century poets of conscience like Czesław Miłosz or Jaroslav Seifert—yet as these names themselves indicate, these “public” poets were overwhelmingly male. The women poets I have chosen never presumed to “speak for the nation” and yet they continually confront some of the most existentially wrenching questions with which the Hungarian nation has faced in the twentieth century and beyond—questions that the men in power have very rarely addressed, under whatever regime you might think of. To me, their moral courage is exemplary.

They also address these questions from a different angle. Sasha Dugdale speaks of the “slow acts of disappearance, [the] cultural and existential elision” of women. (Indeed, I wanted to include the work of one particular woman translator in the volume, but none of her translations were ever accompanied by any biographical notes, and she proved impossible to trace.) Dugdale adds: “There is a point in the writing of every woman poet with the ambition to be truthful to her voice, at which becomes abundantly clear that she cannot write with the voice of her literary predecessors, because they wrote from an entirely different place, and of a different life experience, and she must strike out on her own.”[2]

EH: Following up on this, there is a particular tension in the range of the poems presented here, for instance in Zsuzsa Beney’s “Fugue”—as well as Agnes Gergely’s in “Prayer for Lights Out.” While these poets faced great suffering and destruction, they also retained a particular courage and grace that allowed them to write poems that also generously evoke hope: “let me emit light, while darkness falls.” Let’s start with the life of Zsuzsa Beney, whose personal tragedies were consequential—

OM: Zsuzsa Beney (1930–2006) was a physician by profession and continued her practice up until the age of seventy. (I once met a friend of hers who told me of her deep care and compassion for her patients.) Beney’s first poem was published in an anthology in 1969, her first volume of poetry, Tűzföld (Fireland), appeared in 1970. Altogether, she published nine volumes of poetry, several novels, and four volumes of essays. She also taught at several universities within Hungary, receiving a PhD in literary studies in 1993, and was made associate professor in 1998. She was awarded the highly prestigious Radnóti Prize in 2004.

Beney suffered terrible losses in her own life, particularly the deaths of both her son and husband when she was still in her thirties. Beney does not explore this double tragedy through the lens of individual narrative, but rather through allegory, particularly in her cycle of poems dedicated to the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. As poet and critic Csaba Báthori noted, Beney’s work takes place between the undefined and undefinable metaphysical borderlands between life and death: in her poetry, “we are in that periphery where life and death meet; we must descend into the underworld in order to call a dead person to life; where life continues in death, the dead companion glances back into life . . .”[3]

Beney’s language is spare, she refuses ornamentation, her metaphysics are disembodied. As Sándor Weöres wrote, introducing her in 1969: “[Beney’s] poems are so ethereal that at first, they hardly seem to recognize their themes, it is only after several readings that they begin to emerge. They seem immaterial, a transparent veil, and yet the material that resides within them has been processed in a severe manner.”[4] Beney’s abstract, allegorical approach also had a significant influence on the poets of the post-1989 generation, such as Szilárd Borbély (1963–2014), particularly in its profound movement toward immateriality and abstraction, the working of personal material into allegory, and the incessant questioning of language and material form.

EH: In the case of Ágnes Gergely, she was born the year Hitler came to power and was forced to interrupt her studies and take up manual labor during the height of Stalinism in Hungary. While she was able to finish her university studies, this corresponded with the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution. Let’s explore bit more about her life and her work—

OM: I feel incredibly fortunate to have met with Ágnes Gergely in person in 2024 during a visit to Budapest, and to have spent several hours talking with her and experiencing her ebullient spirit, deep intelligence, and her warmth.

As you mentioned, Gergely was born in 1933 in the small town of Endrőd on the Great Hungarian Plain, where she spent her early childhood. Her family moved to Budapest in 1940, although summers were still spent in the country. In 1944, her father was deported for forced labor and never returned; unconfirmed reports indicate that he perished in Mauthausen.

Gergely attained a degree as a teacher of Hungarian and English in 1957 at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) despite the difficulties presented by her family’s “bourgeois” background. In 1952, Gergely also obtained a vocational certificate as an iron and metal lathe worker after being refused entrance to the University of Theatre and Film Arts for the same political reasons. After earning her ELTE degree, Gergely taught primary and secondary school until 1963, when she chose to begin working as a journalist for Hungarian Radio. Her first volume, You Are a Sign on My Door Post, was published in 1963. In 1973–1974, she was a participant in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. Gergely has published eighteen volumes of poetry and twelve volumes of memoirs and prose, and been awarded over twenty literary prizes, including the prestigious Kossuth Prize. She is also a distinguished and prolific translator from English; her first translations appeared in 1958 and included work by James Joyce and Dylan Thomas.

Over her very long life, Gergely has witnessed an astonishing range of different regimes, including fascism, the early communism of Stalinist Mátyás Rákosi, the late “goulash” communism of János Kádár, the democratic transition of 1989 with its highly imperfect reforms, the euphoric early 1990s (that included the chaos—and destruction—that accompanied unfettered privatization), and finally, the self-proclaimed “illiberal democracy” that has unfolded since 2010 and continues to this day. In total, six radically different forms of governance within one lifetime! And yet, despite its unmistakable moral commitment, Gergely’s work has always remained ethically and artistically independent from any of these prevailing political trends.

EH: As a poet of witness Gergely is a key figure, so let’s continue to speak a bit more about her life and work. Gergely was deeply affected by the death of her father, and her work strives to find deep linguistic channels with which to protect memory—

OM: Gergely has spoken of the extreme difficulty of coming to terms with the deportation and death of her father: “I don’t know when he died and how, which is horrific,” she related in one interview: “That is a truly horrific feeling: person goes into the void, and there is nothing left of him.” And yet she states, “I was shocked by these things, but there is no hatred within me.”[5] Apart from certain poems that address her father directly, Gergely has worked with allegory and symbols—particularly drawing upon her early life experience in the countryside—to convey these realities, interrogating her role in Hungarian society as a woman and as someone of Jewish heritage. In particular, she noted, in her 1978 verse-novel Kobaltország (Cobalt country): “I had no masters. There was no one at whose feet I could have sat . . . Instead, I gained a few glimpses from the classic works of literature that were available to me, truly just a few glimpses. It is precisely because of this apparent fragility that I preserve this long-ago time, just as my favourite gemstone is the pearl, as its form is alarmingly delicate, yet it cannot be polished into pleasingly fitting metal sheets, it does not give up, and it remembers what it was born from.”[6]

It is precisely the way in which Gergely unflinchingly interrogates her own identity as a woman, as a Jew, as a Hungarian, that renders her work so profoundly inspirational and sustaining. The greatest poets always ask the toughest questions—especially the ones that can’t be answered easily, or at all.

As regards memory, Csaba Báthori has characterized Gergely’s work as “the protection of the memories of the memoryless, the preservation of the signs of the dead, an illuminating witness of fidelity. The poetry of Ágnes Gergely employs nearly theological weapons to hollow out its deepest channels. We observe her most characteristic words, word-constellations: doorpost, redemption, preservation, water-ocean, elimination, stone, cemetery-ruin-dust, Old Testament figures, and many times over: sign. The sign which refers to something else, to enigmatic and essential presence, which, completing this life, also directs it, diverts it, verifies it, changes it, vindicates it, renders it meaningful and lifts it up . . . Our impression here is of a long dialogue taking place with those who are distant, a dialogue which determines other aspects of human existence as well . . . [Gergely’s poetry] wishes to reveal something from the world, perchance to exhume something from history, something that, without the help of poetry, would be impossible for us to see.”[7]

EH: The childhood of Magda Székely—born a few years after Ágnes Gergely—was also deeply marked by the Holocaust, with the death of her mother and other family members. These tragedies would play an important role in her poetry. In her poem “The Living,” presented here, Székely explores the fraught role of the survivor, whose responsibility she believes it is to give testimony to those who perished—

OM: Magda Székely (1936–2007) was born in Budapest to an assimilated Jewish family. At the age of eight, she witnessed her mother being dragged away by a gendarme and a member of the Arrow Cross, the Hungarian fascist movement of World War II.[8] Székely was taken to a Catholic monastery—the nuns were openly anti-Semitic, but sheltered her, saving her life—and then placed with Swabian peasants until the end of the war. As Székely herself relates: “My mother was taken away on November 14 in a raid, into the death march that went along Bécsi Street. She wrote two postcards that said: ‘Help me!’ Someone . . . saw her at the border. I don’t know what happened to her after that. If not on the way, then she might have died in an Austrian concentration camp, maybe in Bergen-Belsen. If she even got that far . . . [My cousin and I] were handed over to some lady, then taken to Eskü Square . . . there was a mission of the Swedish Red Cross . . . they were hiding children in various church institutions they had connections with . . .” Székely learned to recite Christian prayers to conceal her identity.[9]

Székely attained her degree in Hungarian and Bulgarian languages in 1959 at Eötvös Loránd University. From 1969 to 1991, she worked as an editor at the prestigious state publishing house Európa Könyvkiadó, then at Belvárosi Könyvkiadó, a new publishing enterprise launched after 1989. She published her first volume of poems Kőtabla (Stone tablet) in 1962. Her second volume, Átváltozás (Transformation) appeared in 1975. Altogether she was the author of nine volumes of poetry, and was the recipient of numerous prizes, including the Kossuth Prize in 2005. She also translated from English, Czech, Bulgarian, and French. The final years of her life were spent in relative seclusion, devoted completely to her writing.

The moral imperative to give witness in Székely’s work is deeply connected to the question of silence. The Hungarian writer and critic András Pályi has noted that silence is “the steadiest of the building blocks of [Székely’s] life’s poetic work, its cohering strength.”[10] There are several words for silence in Hungarian that Pályi cites, some of them indicating the absence of enunciation (elhallgatás, elnémulás), as opposed to silence itself (csönd). Pályi notes that “silence in and of itself is not poetry. But non-speaking, falling silent, is.”[11] In other words, it is a deliberate stratagem of a partial refusal of language, paring it down to its bare essentials, embracing at times as well a refusal of imagery and referentiality.

I read Székely’s “A Drawing” as an ars poetica: “Only a few / darkened lines: / hardly leaving behind / something of itself . . .” The surface of the paper without anything drawn on it, left blank, is “emancipated.” On one profound level, the stark silences and abstraction of Székely’s poetry testify to the moral stance of the survivor who enacts the paradoxical impossibility of representation in the aftermath of genocide on an unthinkable scale and horrifying mental abyss of never knowing the fate of one’s loved ones.

EH: We have also included in this NER feature Székely’s tender poem “Home.” Here Székely calls for the reconstruction of something—a somewhere—which we can call home. As she writes: “Let not these columns collapse // but grow tall, become my safe abode.” This is very much a poem that speaks to our times—

OM: While working on the entire anthology, I felt overwhelmed by how much these poems speak to us specifically now, at a time when authoritarianism and violent intervention are gaining ground across the world, and specifically, when people feeling conflict and climate change are being denied the refuge of a home. It’s a cliché to state that the difference between Western Europe and Eastern Europe is that for Western Europeans, World War II ended in 1945 but that this was not the case in the East—yet I think one must indeed affirm the existence of a stark contrast in how these women poets were so committed to a lyrical and moral processing of the horrific violence of World War II, along with a profound awareness of the afterlife of trauma.

Personally, I do not find this “depressing,” but instead life-affirming. At the same time, there is a clear contrast here with the American postwar poetic canon, which perhaps evolved, at least in part, out of the need to delineate clear ideological differences from other, opposing forms of society, adopting an individualistic and confessional mode, which of course bore many fruits of its own. The poems in this anthology are not, on the whole, confessional or present a call to action—although it is important to mention that one of the poets, Ágnes Nemes Nagy (featured in the anthology but not in this NER selection), took part in the resistance during World War II, fabricating passports and new birth certificates for Jewish friends[12]—but rather, in my view, these poets bear witness to modes of psychic and lyrical survival.

I felt deeply touched by Székely’s “Home.” As an adopted person, whose life commenced with extreme displacement, I find “Home” to be extremely comforting. Perhaps the shelter of which Székely speaks is made of the “wood” of language, of poetry. Sándor Márai, a writer who was not subjected to the same persecutions as the Jewish, Roma, and Sinti communities in Hungary, but who left in 1948 due to his revulsion at the postwar communist regime, spoke of the Hungarian language as his only home, one which sustained him in European and American exile until his death by his own hand in 1989.

EH: Zsófia Balla is a well-known poet, writer, editor, and journalist. Born in 1949, she grew up in Cluj-Napoca, Romania as part of the Hungarian-speaking minority. Like Székely and Gergely, she and her family were also tragically impacted by the Holocaust, and Balla experiened many diffcult years under the Ceauşescu regime. For a decade before 1989 she was forbidden to travel and faced difficulties with publishing. In 1993 she moved to Hungary. Balla’s poem “Afterwards,” featured here in NER, is perhaps one of the most philosophical among this selection—

OM: Approximately one hundred members of Zsófia Balla’s family, including her grandparents, whom she never met, were killed during the Holocaust. Balla’s parents were deported to German death camps but managed to return home after the war. Balla studied violin in Cluj and received a teaching diploma from the Academy of Music in 1972. Her first volume of verse, A dolgok emlékezete (The memory of things) was published in 1968. Balla worked at the Hungarian section of the Cluj radio station until it was closed in 1985 as part of the anti-minority policies of the Ceausescu regime. Between 1983 and 1989 she could not publish her work; nor was she even allowed to leave Romania between 1980 and 1990. In 1993, Balla moved to Hungary, where she has lived ever since.

Banerjee.

Several factors were crucial to Balla’s development as a writer: Of course, the overwhelming and inconceivable loss of most of her family in the genocide of World War II, but also her experience growing up as a member of the Hungarian minority in Romania, and her music school training. In many interviews, Balla has spoken in detail of the importance of all these factors. Many critics have pointed to the musicality of her work, her familiarity with musical genres, and the use of such poetic forms as the chanson and the ballad. Balla has also spoken of the difficulties of existing as a minority-language poet in Romania (in particular during the Ceaușescu years, 1965–1989), her decision to move to Hungary in 1993, and, although clearly drawn to Budapest as the center of Hungarian literary life, having to rebuild one’s life in a city bereft of the scents and sounds of childhood.

Balla herself suggested that I translate “Afterwards” for the anthology, a suggestion I was very grateful for. I consider it to be a deeply philosophical contemplation of an entire life lived in the circumstances of twentieth-century Eastern Europe. “Although I crawled as far as the stars, / I am scorched to the bone by nothingness” to me suggests the profound existential condition of such a life. I am overwhelmed by the raw honesty and lyricism of these lines, of the entire poem, its searching, not for answers, but for a possibility of what might lie beyond.

We have used the pinecone mentioned the poem’s final stanza as the visual motif for the cover of the anthology, in Sunandini Banerjee’s exquisite artwork and design. I feel as if the pinecone, released to the ground by the tree, and yet still opening its “scales” to whatever might come, could serve as a metaphor for the entire volume.

EH: Let’s speak for just a moment also about Zsuzsa Rakovszky, represented in the NER feature by her poem “Song about Time”—

OM: Zsuzsa Rakovszkywas born in Sopron in 1950, where she still lives. Her father passed away when she was a small child. After receiving a teaching diploma for Hungarian and English from Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest in 1975, she first worked as a librarian. Beginning in the 1980s, she began working as an editor, and from 1987 onward, as a freelance writer and translator. Her first book of poetry was Jóslatok és határidők (Prophecies and deadlines, 1981), although it was her second volume, Tovább egy házzal (One house later), that brought her wide attention. Starting from the turn of the millennia, Rakovszky began writing prose as well, publishing several acclaimed novels. In 1990, she participated in the International Writing Program of the University of Iowa. Her poetry has been translated into English by George Szirtes (New Life, London, Oxford University Press, 1994), and her bestselling novel Shadow of the Snake appeared in German, Italian, Bulgarian, and Dutch.

As Beatrix Visy has noted, Rakovszky’s poetry, lyrical in nature, is characterized by its rootedness in the “thrownness” of existence (Heidegger’s Geworfenheit, or “the state of being thrust into this world”), and the confrontation of human space and time with the infinite. Within space, time may become embodied, and within these forms of space, it gains content and relations to other forms and objects.[13]

The inevitable descent into ruin and obsolescence of the products of early socialism is a strong theme that runs throughout Rakovszky’s work, and the inevitable “uselessness” of these objects may recall Walter Benjamin’s well-known analysis: “The other side of mass culture’s hellish repetition of ‘the new’ is a mortification of matter which is fashionable no longer.”[14] And yet these objects do not follow their trajectory in time alone—attached to them are fates, the fates of the “small lives” of the provinces. Previous epochs of early socialism (the time of the poet’s childhood), the interwar years, and the more distant, fading yet indelible memories of the Habsburg Empire, are juxtaposed through a surrealistic clash of objects whose half-lives, even as broken and useless items, indicate a refusal of the past to be buried—a subtle critique of the “politics of forgetting” which seems to be the perennial feature of just about every regime in this part of the world.

Many of these poems are haunted by the uncanny, the Unheimlich, in which the boundaries between everyday life and the specters of the past are more than mutable: these specters can breach the frail membrane of the present at any time. Rakovszky posits the poem as a haunting, the poem as hauntology, drawing us to the multilayered palimpsest of the past through the word, the “presence made of absence,”[15] a lyrical intervention reminding us that, surrounded by the detritus of a “past and useless age,” its material objects—and the people who held those objects in their hands—enduringly exist on another plane and continually intersect with ours.

EH: Finally, Krisztina Tóth (b. 1967) is a well-known contemporary Hungarian author of both poetry and fiction. In the selections presented here, we witness her creative strategies of using unexpected viewpoints and images. While the older Hungarian women poets faced wartime and postwar challenges, it appears this is not entirely a thing of the past. Due to the changes in the political climate in Hungary, in 2010 Tóth chose to relocate due to government pressure and other threats—

OM: Krisztina Tóth studied sculpture at the Vocational High School of Fine and Applied Arts in Budapest, graduating in 1986. After working briefly in a museum, she enrolled at the Faculty of Arts at Eötvös Loránd University, and spent a period of time studying in Paris, where she began translating French poetry. She completed her university degree in Hungarian in 1992 and was employed by the Budapest French Institute starting in 1994. From 1998 onward, she has been a freelance writer. Tóth has published nine volumes of poetry, eleven volumes of prose, and dozens of books for children, with her work translated into eighteen languages. Her novel A majom szeme (Eye of the Monkey)[16] was a bestseller in Hungary in 2022.

Just as the poets born earlier in the twentieth century were forced to deal with the legacy of World War II and its aftermath in Hungary, Tóth—as was the case with many of her contemporaries—inevitably found herself forced to deal with the chaotic circumstances that ensued in Hungary in the 1990s after the sudden, unexpected cessation of late communist rule. It is difficult not to see at least some of the profound disillusionment associated with the failed promises of 1989—the onset of massive corruption, the monetization of so many aspects of life, the non-transparent privatization of state enterprises, and, as George Szirtes comments,[17] the rupture of many personal relationships—as informing Tóth’s subsequent oeuvre, both in prose and poetry. While it is true that Tóth’s work is characterized by a certain “obscurity/uncertainty (dream-like states),” as Viktória Radics points out, it also contains “hyper realistic details”[18] that point with extreme specificity to everyday life in post-communist Hungary. The musicality of her verse, as well as its formal perfection (including the use of colloquial elements of speech), mean that the otherness (to use Radics’s term) portrayed in her work is even more eerie.

Tóth’s creativity is vast, including not only her literary work but her achievements as an accomplished stained-glass artist and her translations of over twenty volumes from French. Like the fleeting play of briefly glimpsed lights and reflections in glass, Tóth’s poems stand apart from epic narrative. Rather, they form delicate, exquisite miniatures in which seemingly banal instances of middle-class European daily life in the early third millennium are infused with sudden twists of meaning, leaning at times towards a strong sense of surrealism.

Yet any discussion of Tóth’s work, unfortunately, cannot remain unaffected by the circumstances of her life even in the (semi-) open society of contemporary Hungary. After Tóth commented in an online literary magazine in 2021 that two “classics” in the national literature curriculum should perhaps be exchanged for books that represent more positive gender roles for girls, a campaign of cyber-bullying and cyber-hate followed, including harassment on the street where Tóth resided in Budapest and excrement dumped in her mailbox.[19] She and her family, including her adopted daughter of Roma origin, were obliged to relocate abroad. The enormous price Tóth has paid for speaking up about gender issues in Hungary—even within the context of a number of questions posed by an online literary magazine—is a deeply distressing reflection on the state of gender equality in Hungary today.

EH: These Hungarian women poets, along with the four others featured in Under a Pannonian Sky: Ten Women Poets from Hungary, give us an essential introduction to the immense talent and courage of two generations of Hungarian women writers. All of these writers have faced the vicissitudes of History, and yet maintained their courage and humanity in the face of extremity. In our current climate of the uncertain return of History, you have given us a gift from which we can learn. Thank you and all the other translators who particiated in this project for making this precious work available to us in translation.

OM: Thank you. Altogether, the volume is the work of six other translators besides myself—Anna Bentley, Erika Mihálycsa, Ivan Sanders, Clare Pollard with Anna T. Szabó, and George Szirtes. Without their contributions, this anthology could not have come together, so I am deeply grateful for their efforts, and of course, for the work of the poets themselves, who collectively have provided me with a kind of guiding light that has been present throughout my entire life. This volume is intended as a deeply felt, personal homage to the immensity of their achievement.

[1] Ágnes Lehóczky, Poetry, the Geometry of the Living Substance: Four Essays on Ágnes Nemes Nagy. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative and Critical Writing, University of East Anglia, School of Literature and Creative Writing, 2011, p. 20.

[2] Sasha Dugdale, Introduction, Trust (Claire Pollard with Anna T. Szabó trans.) (Todmorden: Arc Publications, 2021 ), p. 12.

[3] Csaba Báthori, Már csönd se vagy – Beney Zsuzsa (1930–2006) (Now, you are not even silence – Zsuzsa Beney [1930–2006]). Magyar Narancs, July 20, 2006.

[4] Quoted in János Szegő, Áttetsző sűrűség (Transparent density), revizoronline.com. May 5, 2008.

[5] Interview with Ágnes Gergely: “I know I have a guardian angel, sometimes it appears in my dreams,” hlo.hu, March 16, 2022.

[6] Ágnes Gergely. In Kobaltország. Egy jazz-koncert után (Cobaltland. After a jazz concert). https://reader.dia.hu/document/Gergely_Agnes-Kobaltorszag-852

[7] Csaba Báthori, A tisztaság íze (The taste of integrity). Élet és irodalom, volume XLIX., no. 26, July 1, 2005.

[8] Magda Székely, Éden (Eden) (Budapest: Belvárosi könyvkiadó, 1994), pp. xxxvii–xxxviii.

[9] Quoted in András Pályi, Székely Magda csöndjei (The silences of Magda Székely). Kalligram, Vol. VII, January–February 1998.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Lehóczky, p. 19. Lehóczky notes that Nemes Nagy and Balázs Lengyel were given the Yad Vashem Award by Israel posthumously in 1997.

[13] Beatrix Visy, Az idő és a tér csapdájában (In the snare of time and space), Élet és irodalom, Vol. LXVII, no. 41, October 13, 2023.

[14] Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 1991), p. 159.

[15] Cited in Sadeq Rahimi, The Hauntology of Everyday Life (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021) p. 12.

[16] English translation (Ottilie Mulzet), Seven Stories Press, New York, 2025.

[17] Introduction. In: Krisztina Tóth, My Secret Life: Selected Poems (George Szirtes trans.) (Hexham: Bloodaxe, 2025), p. 12.

[18] Viktória Radics, Emberruhában (In human attire), Holmi, Vol. 22, no. 11, November 2010, p. 1475.

[19] See: https://hlo.hu/news/hlo-in-support-of-krisztina-toth.html.

Ellen Hinsey is the international correspondent for New England Review. She is the author of nine books of poetry, essays, dialogue, and translation. Her most recent books include The Invisible Fugue (2024) and The Illegal Age (2018), which explores the rise of authoritarianism. Hinsey’s essays are collected in Mastering the Past: Reports from Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe (2017). Hinsey’s other poetry collections include Update on the Descent, The White Fire of Time, and Cities of Memory (Yale University Series Award). Magnetic North, Hinsey’s book-length dialogue with Tomas Venclova on totalitarianism and dissidence was a finalist for Lithuania’s book of the year. Her work has appeared in publications such as The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Irish Times, Poetry, and New England Review. A former fellow of the American Academy in Berlin, she has most recently been a visiting professor at Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany.

Ottilie Mulzet has translated over nineteen volumes of Hungarian poetry and prose from contemporary authors such as László Krasznahorkai (winner of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature), Szilárd Borbély, Gábor Schein, György Dragomán, László Földényi, István Vörös, Edina Szvoren, and others. Her translation of László Krasznahorkai’s Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming was awarded the National Book Award in Translated Literature in 2019. Her translation of Krisztina Tóth’s Eye of the Monkey is forthcoming from Seven Stories Press in October 2025.

This interview is part of the thirteenth installment in our “Literature & Democracy” series, which presents writers’ responses to the threats to democracy around the world.

Subscribe to Read More