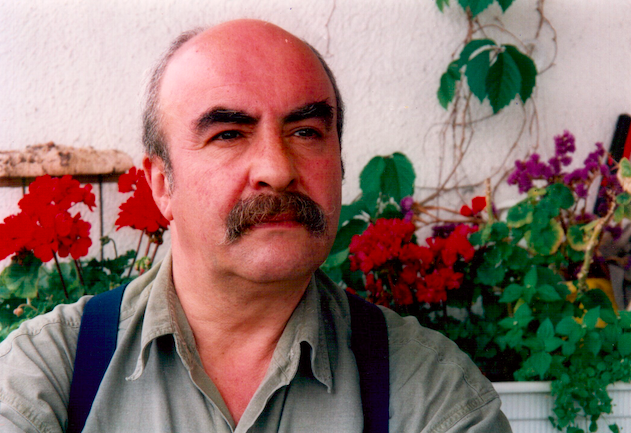

Moisei Fishbein

NER international correspondent Ellen Hinsey talks with translator Ostap Kin about Ukrainian poet Moisei Fishbein’s upbringing, identity, and “outsider modernist” poetry.

Ellen Hinsey: Moisei Fishbein passed away in 2020, and his work is just now gaining a larger readership via English translation. Let’s start by speaking a bit about his life. Fishbein was born just after the end of the Second World War, in 1946, in Chernivtsi, Ukraine. The postwar world of his childhood was characterized by many challenges, including famine, material shortages, ongoing displacements, and other difficulties.

Ostap Kin: Moisei Fishbein’s father was initially from Bessarabia and his mother was a Ukrainian language high school teacher from what is now the Mykolaiv region in southern Ukraine. After the war, the family settled in Chernivtsi (Cernăuți in Romanian, Czernowitz in German), a city with a complex past. Part of Moldavia, a historic province of Romania, over the centuries it found itself under the control of various great powers. In the nineteenth century it was under the Austro-Hungarian empire; during the interwar period it returned to the Kingdom of Romania. In 1940 Chernivtsi was occupied by the Soviet Union, and in 1944 incorporated into the USSR. The city, however, remained multi-ethnic and multilingual: Fishbein’s parents spoke Ukrainian and Yiddish interwoven with Russian—and Hebrew was the language of religious practices. Romanian was still spoken in the city. This multilingual background was a significant part of Moisei’s upbringing and identity. The postwar years, especially in contested cities like Chernivtsi—and in other places incorporated into the Soviet Union—were a time of tremendous challenges. This meant (re)organizing life to cope with the new postwar Soviet reality and newly established order and rules.

EH: Let’s speak a bit more about the multicultural and multilingual character of Chernivtsi, which created such a unique artistic environment—

OK: During the interwar period, Chernivtsi was a vibrant cultural center, known for its flourishing linguistic diversity. It was a place where Romanian, German, Yiddish, and Ukrainian cultures overlapped and intertwined, creating a rich tapestry of intellectual exchange. The city was a significant intellectual hub for all these communities. The influential Ukrainian modernist and feminist author Olha Kobylianska spent most of her creative life there. A true constellation of German-language authors inhabited the city, including Paul Celan and Rosa Auslander. It was also a place of particular significance for the Yiddish language: The famous 1908 international Yiddish conference took place there, and one of the last Yiddish-language writers in Europe, Yosyp Burg, resided and then passed away in Chernivtsi some ten years ago.

EH: Fishbein was initially interested in the theater, but his parents convinced him to study engineering. This led to him to enroll in Novosibirsk University’s Department of Economic Cybernetics in Akademgorodok, Siberia. This was not a particularly good fit for the poet—

OK: Because of the state-orchestrated anti-Semitic campaigns and Jewish quotas, it was difficult to enroll in Soviet Ukraine university programs. Thus, one option was to relocate to Siberia and try to attend a program there. Curiously enough, at the university in Novosibirsk, there were a substantial number of students from Chernivtsi—around sixty or so—and they ended up forming a kind of close community. At the university, these students held an annual literary festival. On one occasion Fishbein invited the already prominent Ukrainian poet Ivan Drach to participate. Fishbein showed Drach his poems, and the latter eventually helped him to place some of them in a Kyiv-based literary journal. He also put Fishbein in contact with Mykola Bazhan, a living legend, who was responsible for introducing the generation of writers who started out in the 1960s to the history of Ukrainian avant-garde and modernist literature, which had flourished in the 1920s and 1930s.

EH: Fishbein eventually moved from Novosibirsk University to Odessa University, and from there to the Kyiv Pedagogical Institute. Once in Kyiv, his work began to circulate, and his first volume of poetry was prepared for publication—

OK: Fishbein’s unwavering desire to be closer to Ukraine, and to become involved in Ukrainian letters is a testament to his resilience. Mykola Bazhan, whom I just mentioned, played a pivotal role in his return to Ukraine. Despite the challenge of not being able to immediately relocate to Kyiv, Fishbein’s determination led him to take steps that would eventually facilitate this. At a certain point, Fishbein was drafted into the Soviet army, which was mandatory for all Soviet men. His service led him to the Far East, an experience that also has significant echoes in his writing.

EH: The 1960s and 1970s saw, throughout the Soviet Union, the creation of literary and dissident circles. This was met with resistance from the Soviet authorities. The early 1970s in Ukraine were characterized by significant repression against the intelligentsia and writers—

OK: The 1960s in the Ukrainian literary tradition are known as the period of shistdesiatnyky (the “people of the sixties”), i.e., those poets who came of age during that decade. This period can also be seen as the second Soviet Ukrainian wave of modernism. It was a period of active experimentation, which also bridged different Ukrainian modernist traditions and modes of writing. Above all, it was a period of rediscovery of the writing of the “Executed Renaissance,” the Ukrainian authors whose work had flourished during the 1920s and 1930s, many of whom had perished during Stalinism.

By the end of the 1960s, however, the authorities had curtailed this second literary flowering and ushered in a new era of repression. Surprisingly enough, one of the areas left relatively untouched was translation. This was a literary space where poets could not only still earn their living by producing translations, but where they could experiment and—what was equally important—get published and be compensated.

EH: In many ways, Fishbein’s life reflects the archetype of the exiled poet of the twentieth century, particularly from the Soviet space. His case reminds us very much of the Lithuanian poet Tomas Venclova. In the mid-1970s Fishbein was invited by the KGB to a profilaktika or “prophylactic” talk, where individuals would be intimidated, or pressured into becoming informers—

OK: As part of the Ukrainian intelligentsia in Kyiv, Fishbein was in contact with those who later would be called “dissidents”—this was his milieu. The authorities, of course, wanted information about this world, and Fishbein refused. As his widow recalled, Fishbein would say that he had been given the choice between being “sent to the Far East” (meaning to some sort of Soviet labor camp) or “the Middle East” (meaning a forced exile away from Ukraine, a place he did not want to leave). In the end, Fishbein was sent into exile to Israel.

EH: Fishbein remained in Israel only three years, choosing instead, in 1982, to settle in Germany, where he worked for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Munich on Ukrainian topics—

OK: During this period, Fishbein’s connection to Ukraine remained profound: he secured a position with Radio Liberty in Munich, working with them as a correspondent, editor, and translator. His colleague, Igor Kachurowskyj, a poet of note, a discerning literary critic, and a relentless scholar of Ukrainian versification, played a significant role in Radio Liberty’s hiring of Fishbein. Fishbein also considered the Voice of America, then based in Washington, D.C., but chose Radio Liberty in order to remain closer to Ukraine—a country that still seemed unreachable in 1982. Fishbein worked at Radio Liberty until the mid-1990s, when the service was relocated from Munich to Prague. In 1989, during the perestroika period, Fishbein was finally able to begin traveling back to Ukraine.

EH: We began this conversation by speaking about Chernivtsi, the city of Fishbein’s birth. This city was, of course, as we discussed, also the birthplace of the great German-language poet and holocaust survivor Paul Celan. This overlapping of destinies was important to Fishbein, and in his work we feel Celan’s influence—or perhaps one might say the dialogue Fishbein is carrying out with Celan and his work.

OK: This is one of the most mysterious transformational connections in this story. Celan, born in Chernivtsi in 1920, left his hometown for Bucharest in April or May 1945. A little more than a year later, Fishbein was born in Chernivtsi in 1946. Fishbein would become involved with Celan’s work in the early 1970s. The poet Mykola Bazhan gave Fishbein his unpublished Ukrainian translation of Celan’s famous poem “Todesfuge” and asked Fishbein to visit Chernivtsi and locate places and spaces related to the late poet. Fishbein found the house where Celan had lived, some people who had known Celan during the interwar period, and the grave of the poet’s uncle, among other important things. Later, Fishbein would also translate Celan into Ukrainian, and significant intertextual details are visible in his own poems.

EH: Moisei Fishbein’s poems featured here in the New England Review speak to a universal sorrow and grief—one that seems inescapable. The poems are particularly poignant when today many, worldwide, cannot believe the level of violence human beings are still capable of carrying out. In this, poetry has no borders.

OK: It might be worth noting that Fishbein’s poetry can be aptly described as that of an “outsider modernist.” His work can be seen as incorporating a number of modernist traditions from the West, creating a dialogue that is both intriguing and thought-provoking. He draws inspiration from, and is in a dialogue with, poets such as Rainer Maria Rilke, Gottfried Benn, and Charles Baudelaire, as well as many others. Even though his literary debut took place in the 1970s—one of the most suffocating periods in the history of Ukrainian Soviet literature—his work was already reflective of the poet’s profound and intricate approach to texts. We observe the need for experimentation, along with a thirst for novelty when it comes to building a poetic world.

EH: Fishbein returned to Ukraine in 2003 and found his place there amid the momentous events that were unfolding. Fishbein’s voice was for unity and for making a place for the diversity that exists in Ukraine—

OK: Exactly—and he also kept writing poetry. In those poems, we recognize Fishbein’s voice, one that we cherish. He continued to produce innovative writing—and he never stopped experimenting.

Moisei Fishbein (1946–2020) was an award-winning Ukrainian poet, essayist, and translator, author of the collections Iambic Circle (1974), Collection Without a Title (1984), Apocrypha (1996), Scattered Shadows (2001), Early in Paradise (2006), Prophet (2017), a collection of children’s poetry, Wonderful Garden (1991), and translations from many languages including German, French, Italian, Hebrew, Polish, Russian, Spanish, Catalan, Romanian, Hungarian, Yiddish, and Georgian. A collection of his translations of Rainer Maria Rilke into Ukrainian appeared in 2018. He was a recipient of the Vasyl´ Stus Prize, the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, the Order “For Intellectual Courage” (awarded by the journal Yi), and the Omelyan Kovch Award. He was a member of the Ukrainian Center of the International PEN Club and the National Union of Writers of Ukraine. In 1979, Fishbein was forced to leave the Soviet Union. In the early 1980s, he worked at the journal Suchanist’ (Munich/New York), a venue of literature, politics, culture, and the arts. Before moving in the early 1980s to Munich (Germany), where he took a job as a writer, editor and correspondent for Radio Liberty/Radio Free Europe, he lived in Israel. Fishbein returned to Ukraine in 2003. His poems have been translated into German, Hebrew, and other languages. His poems in English translation have appeared in AGNI, Modern Poetry in Translation, and various anthologies.

Ostap Kin is the editor of Babyn Yar: Ukrainian Poets Respond, which received an honorable mention for Best Translation Prize from American Association for Ukrainian Studies, and New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City, which won the American Association for Ukrainian Studies Best Translation Prize. He is the translator, with John Hennessy, of Yuri Andrukhovych’s collection Set Change (NYRB/Poets, 2024), the anthology Babyn Yar, and Serhiy Zhadan’s A New Orthography, which won the Derek Walcott Prize and was a finalist for the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. He translated, with Vitaly Chernetsky, Yuri Andrukhovych’s collection Songs for a Dead Rooster. His work appears in the New York Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Poetry, World Literature Today, and elsewhere.

Ellen Hinsey is the international correspondent for New England Review. She is the author of nine books of poetry, essay, dialogue, and translation. Her most recent books include The Invisible Fugue (2024) and The Illegal Age (2018), which explores the rise of authoritarianism. Hinsey’s essays are collected in Mastering the Past: Reports from Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe (2017). Hinsey’s other poetry collections include Update on the Descent, The White Fire of Time and Cities of Memory (Yale University Series Award). Magnetic North, Hinsey’s book-length dialogue with Tomas Venclova on totalitarianism and dissidence was a finalist for Lithuania’s book of the year. Her work has appeared in publications such as the New York Times, the New Yorker, the Irish Times, Poetry, and New England Review. A former fellow of the American Academy in Berlin, she has most recently been a visiting professor at Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany.

Subscribe to Read More