A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

He passed the stages of his age and youth . . .

—T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922)

YOU WILL SEE

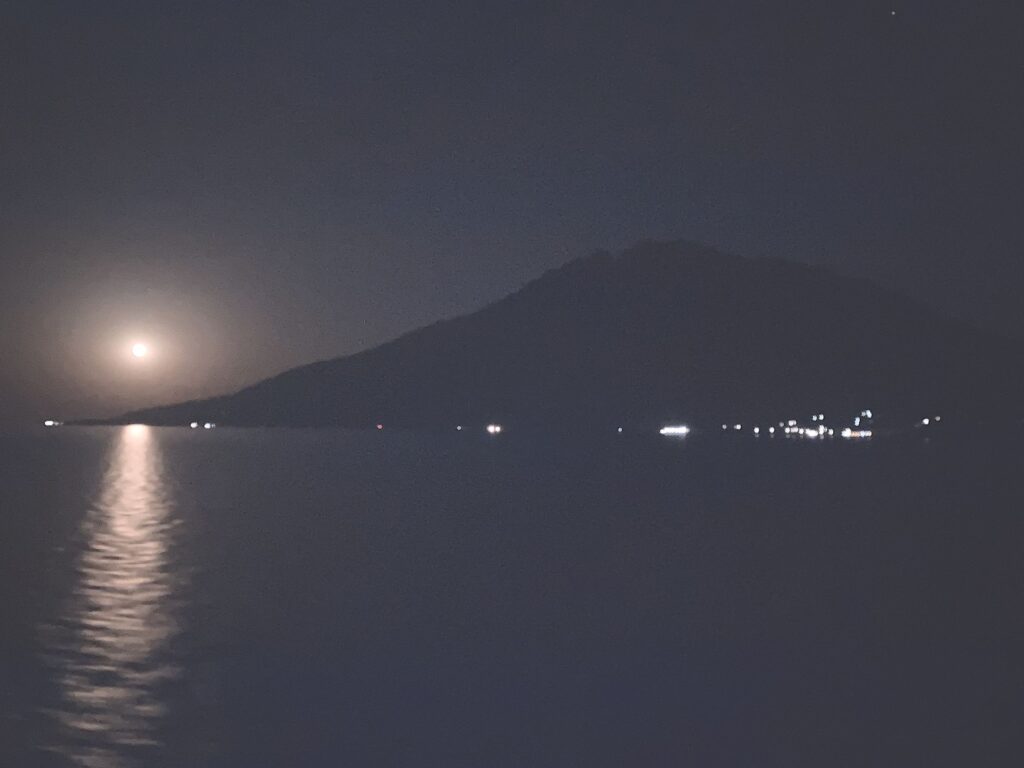

From far away, Samothraki doesn’t look like a people-eater island. It is a mound, furry, the shape of the snake in The Little Prince after it has consumed the elephant. And now, it is sleeping. I draw a plastic deck chair close to the railing and open my Mythos beer, staring out at the Thracian coast and the skeletal shape of Alexandroupolis crumpling behind me. Far out there, the waters are said to change nationality, but I cannot make sense of it. The patrol boat speeds past our ferry, its blue and white cross fluttering towards Turkey.

I have been warned that each year there are unexplained deaths on Samothraki. The hotel owner in Thessaloniki flinched at my destination: “I wouldn’t go there. Bad things happen to people on Samothraki.” In Donousa, the brothers running the beach taverna said, “The island is very strange. You will see.” But the café owner in Athens had visited with his wife. When they arrived in Samothraki with the ferry, she stepped to shore, walked only ten meters onto the island, before turning right around to reboard the boat. When asked why, the man replied with a frown, “It’s a feeling. You will see.”

I was told I should be careful on the island of accidents: of sinkholes, waterfalls, whirlpools, cliffs, and snakes. There are trails where you can climb up but not down. The peak, Fenghari, might as well be translated as “certain death without a guide.” The earth could open in the night, leaving no one wiser to your fate. And then there is the river, Fonias, whose name literally does mean “killer.” Listening to the brothers, I made a mental note of this toponym, Fonias, especially when told that its highest reaches offer the most beautiful pools and views in the Aegean.

Mount Fenghari now looms higher above our little boat. Poseidon watched the Trojan War from it, “high on the topmost peak of wooded Samothrace,” or so says The Iliad. The summit this late afternoon is not visible, but I have seen pictures of the 1,500-meter volcanic cone, of the kind you’d expect in the Pacific, not in the northern Aegean. Clouds now seep down the obscured slopes, leaving shadows, warped dark shapes cast on other vapors, slipping into the sea.

The island is armed against visitors as there is no natural harbor. Samothrace’s isolation means historically it has depended on its own cereals and oils and developed an unusual form of Greek. I imagine it is also spoken by the inbred animals and unique plants.

As I take the stairs deep into the ferry, the island disappears until the vessel lowers its rusty gangway, so I can disembark with six Bulgarian tourists and four scrawny hippies on motorbikes.

I wonder whether I will also walk only ten meters onto the island before turning around. But I am distracted as we disembark because we are forced to pass to one side. There are twenty people waiting to travel to the mainland under armed guard. They are lined up quietly, with uniformed officers at the head and tail of the queue. I notice that most are young men with darker complexions than the Greeks. A woman is unveiled, with two small children at her feet, one of whom runs out from the group, and she calls after him, her hesitant move halted by the guards’ watch.

But by now, I have passed the refugees and do not see what happens next. I continue another ten meters. Is that uneasy feeling—of something hollowed, from underground—suggested by the stories I have heard, or is it the sound of the island waking?

AKRAM

Akram was already there, although I came a little early. I suspected he had, by now, also spent long enough in Germany to be terrorized into über-punctuality. He had brand new sneakers and an Adidas T-shirt, on a day hot for October—not like last year when he was shivering from cold outside Berlin’s refugee processing center, LaGeSo, where I’d volunteered on and off a few weeks in 2015, because I spoke a smattering of Arabic. Akram waited an undignified length of time for his number to be called. And now, he shows me with pride his Studentenwerk card, preloaded with credit, to use in the cafeteria of the Humboldt University, where he chitchats with the woman in hijabat the register, as he insists on buying me my chicken in peppers and mashed potatoes, and a KitKat, even if I don’t want a KitKat, but he says, “Have a KitKat, I know you want a KitKat”—and I know well enough not to refuse.

He’s been a student before. More than a year earlier, in Damascus, he decided with a group of friends on a rooftop that it was time to leave. The faculty had been bombed that afternoon, and he had seen a lecturer crawl out of his own blood. A few days later, with American dollars in their pockets, they were on a bus to Beirut, a flight to Turkey, and then standing on the Aegean’s shore, staring out at Greece.

Akram had told me it was unreal to be woken in their hotel in the middle of the night, after only a couple hours of sleep, and be dispatched quietly into a van. It took them to the rafts, which were overloaded when they were pushed into the water. Children held onto ropes, and their boat sat so low that the larger waves lapped into it.

The raft traveled out to sea. All the surfaces were wet, their feet were drenched, and it was cold. The shore was still visible when someone must have shifted position, or the weather turned, and the raft began to sink.

Most chose the sea amid the panic and screams, and a father even threw his baby first before leaping in to save him. The strongest swimmers dragged the half-submerged boat hundreds of meters back to the launch where, reduced to tears, half of the refugees—especially those with children—refuse to reboard, even if it meant losing everything they had paid.

“I remember,” Akram tells me, pushing his lunch tray to one side, “that I had a cigarette I kept dry in a ziplock bag. I took it out and smoked it, looking at the water as the sun rose. I thought: this might be my last cigarette and my last morning ever on a beach.”

Then Akram got on the boat again—because “what happened was an accident, and I wasn’t about to let my life go to pieces over that”—and they pushed off with a lighter load. As the dawn grew rosy, the island with its tall peak rose above them, and they did not know whether the approaching patrol boat was Turkish or Greek. Only when it was very close did he understand he was not going to be sent back. That now, having passed over this graveyard of the unlucky, he was not going to die.

I walk with Akram after lunch through the eighteenth-century halls of the university towards the monumental, red marble staircase at the Unter den Linden exit. I congratulate him before we part ways, but also ask something on my mind: does he plan to go back to Syria after he finishes his degree? But I regret the question as soon as it’s asked, because there is still no end to the war in Syria, and who am I to suggest how he should spend his life. And Akram shrugs, one that also seems directed at all the pomposity of the entrance hall with its classical flourishes, and he says vaguely: Insh’allah.

At the top of the stairs, I say goodbye to him, and then, after I have descended halfway down the marble, I turn back. I see that he is still there, standing very still.

PLUMAGE

Charles Champoiseau was twenty-seven years old when he was appointed French consul to Adrianopolos (today’s Edirne, on the Greek-Turkish border) in the Ottoman Empire. At the start of his career, he had little experience with only two minor postings near the Black Sea behind him. Why the man from Tours, as an amateur archaeologist, came to Samothraki in 1862 is unknown, but he soon began excavating a site on the northern slope of Fenghari. Known as the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, this place attracted pilgrims from all over the ancient world for more than a thousand years celebrating the island’s mysteries until their demise in the fourth century AD. When Champoiseau arrived, centuries of pink laurel trees had grown over the site, burying strata of archaic, classical, and Hellenistic antiquities.

On April 15, 1863, working on the western terrace, he discovered pieces of a statue: a torso, and many small fragments, which were wings. In a letter dated the same day, he wrote to the French Ambassador in Constantinople:

Monsieur le Marquis,

Just today, while excavating, I found a statue of the Winged Victory (by all

appearances) in marble and colossal proportions. Alas, I do not have the head or

the arms unless I find pieces of them while excavating in the surrounding area.

What remains, comprising the lower breasts to the feet (2m 10cm) is almost

entirely intact and crafted with an art that I have not seen surpassed in any of the

beautiful Greek works that I know . . . the draperies are the most exquisite that one

could imagine: a veritable chiffon of marble, stuck by the wind to living flesh. All

that without a hint of hyperbole.

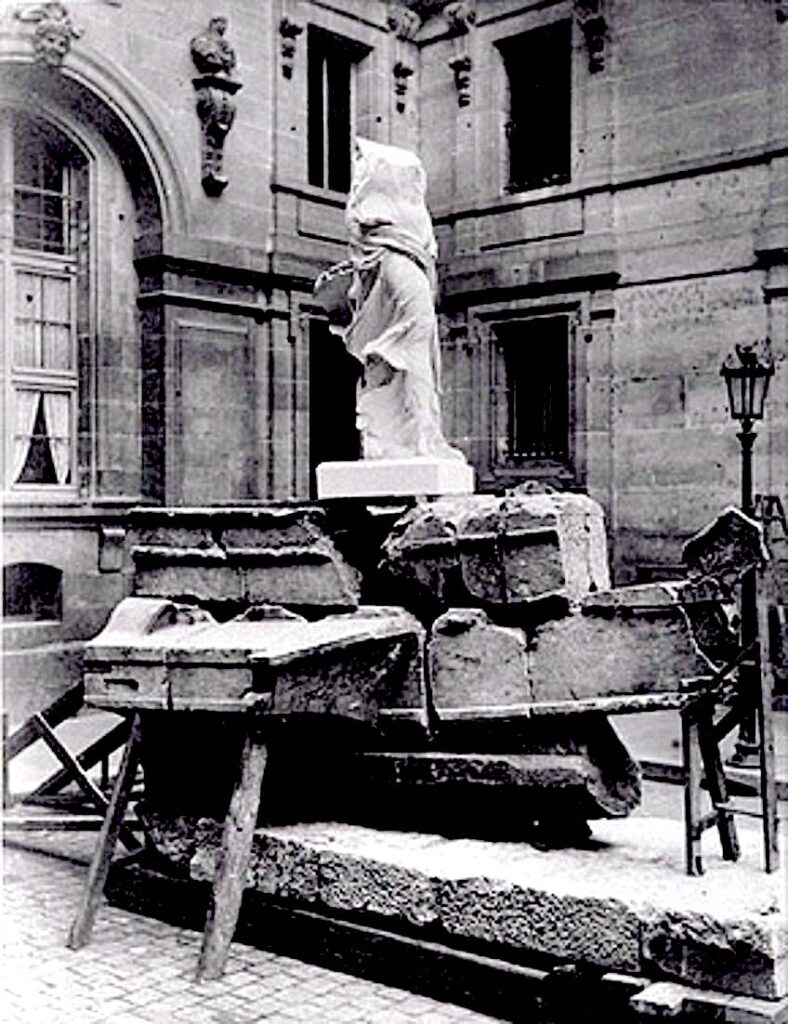

The second-century BCE marbles would become known as the Winged Victory of Samothrace, antiquity’s most famous statue.

Only later did archaeologists find the pedestal, representing a ship’s prow, on which the statue stood as it stared down on the natural amphitheater of the holy grove towards the sea. It was most likely dedicated to a naval victory. The sea is also on her figure, as if she still parts the waves. At one moment, she appears to create her own weather, the ripples on her clothing casting up a gale. The next, she is drowning, even in the dry air of a museum, as she stretches against the ropes holding her ravaged garments in place. Only the enormous plumage promises her escape.

Champoiseau continued in his letter to the counsel that the major obstacle in removing the statue to France was that it was too heavy. The Parian marble weighed up to 1,500 kilograms, and since Samothrace’s coastline provided difficult anchorage, the move was certainement impossible.

Not dissuaded, the French government had all the small pieces of the statue sent ahead before dispatching a vessel, L’Ajaccio, to the island. The Herculean task of bringing the big blocks a half kilometer down to the sea, by hoist, pully, and rolling cart, began. The locals did the heavy work and watched the pieces of their discovery sent north.

I stand on the sanctuary’s hillside, put one thumb to the air, and imagine L’Ajaccio veering perilously from the coast.

Did the statue peek through her crate’s slats during her voyage? First, to the minarets of the Bosphorus, and then, as the boat approached Piraeus, to the hazy Acropolis? The ship continued west. Perhaps the sailors manning the liner to Toulon heard fluttering, or found a feather blown down the port side. She waited in storage for six months at the French dock before the funds were released for her transport to Paris.

Salvaged from the sea, from the earth, and reassembled after millennia spent in pieces, she is now installed famously in the Louvre museum, very still at the top of a staircase.

WHEN IT WANTS

I could be quite happy not leaving this room in Therma, a small town on the northeastern side of Samothraki. It’s probably safer, too, given what I have heard of the island. The room is like those all over Greece that appeal to my Spartan instinct to live an uncluttered life: tiled floor, wooden bed, white sheet, fleece blanket, and a quilt in the wooden wardrobe for cold nights or when Fenghari’s shadow passes over the garden. The mountain is visible from the double doors past the neatly swept terrace.

I am alone in the B & B except for the family who live in the next house. I can feel the hollowness of the unoccupied rooms when I walk down the hallway to the kitchen, which has the expansive feeling of being only for me. I lie in bed and listen to birds chirping, wind in trees, and the occasional rumble of the refrigerator with my yogurt and apricots in it. Then, I catch a whiff like semen from a plant, a smell caught in the curtains until the wind rises again.

I’d asked Anastasia earlier that evening if it was safe to drink the tap water, and she replied, “more than safe.” I take a glass, fill it from the bathroom sink, and find that it is thicker than normal, something exuded from the earth, something I suspect will keep me here. By the week’s end, I am likely to look twenty years younger. But if I ever leave the island, the enchantment will reverse, piling years on me. I will head back to Berlin an old man, or in pieces.

It’s twilight, but I hang up my clothes in the garden. Anastasia let me use the washing machine when I arrived. Thick is the adjective I would use also for the night air, and it gets even more so the farther I follow the clothesline to the edge of the garden where, busy with my domestic task, I am startled by a light that breaks red through the mist. Where the garden lawn ends, I can see the moon rising to the east, from Fenghari.

When I wake, the vapor has lifted, the sun pouring in from the terrace. The fruity fragrance is perhaps from the enormous flower domes hanging over the window frame. I see Anastasia taking down my underwear and folding them.

Barefoot on the lawn, I try to take over, mentioning that my plan today is to look for the river I’d been told about, the one they call “the killer.”

Anastasia stops. Her hands full of my clothes, she exclaims, Mein Gott. Like many of the islanders, she spent many years working in Germany.

I casually examine her concern.

“Be careful. They call it that for a reason!”

I cock my head.

She replies that the river has the bad habit of flash-flooding: “The waters rise suddenly, and there is no time to react.”

I stop smiling. “At this time of year?”

“Normally earlier in the spring. But nobody can predict it,” she says, considering, before saying, “When it wants.”

“When it wants.”

“Yes.”

“So, I just hope for the best—”

“Or you don’t go.”

“Or, I just hope for the best.”

She gives me a tough smile. “You will see.”

“I keep hearing that,” I reply.

—

At the end of the garden is a gate, and I follow a small road from it out of Therma. From far away, Samothraki looked rocky, sheer, inhospitable. Here, the chestnut trees are clouds competing in density. Cedars have enormous trunks, the underbrush is impenetrable, and the plane trees are crowned by halos of spring green. Everything is buoyed by moisture and bursting with oxygen. Light passes visibly through the summer haze; all is seen as if through a grainy filter, as the path turns into the mottled forest, and I hear running water from streams and waterfalls but cannot see them.

I hitch a ride farther east, along the coast, sitting in the back of a pickup truck, as the dense air is rippled away by the speed, and I get off where the sign indicates another trail that heads directly to the mountain—“Fonias.”

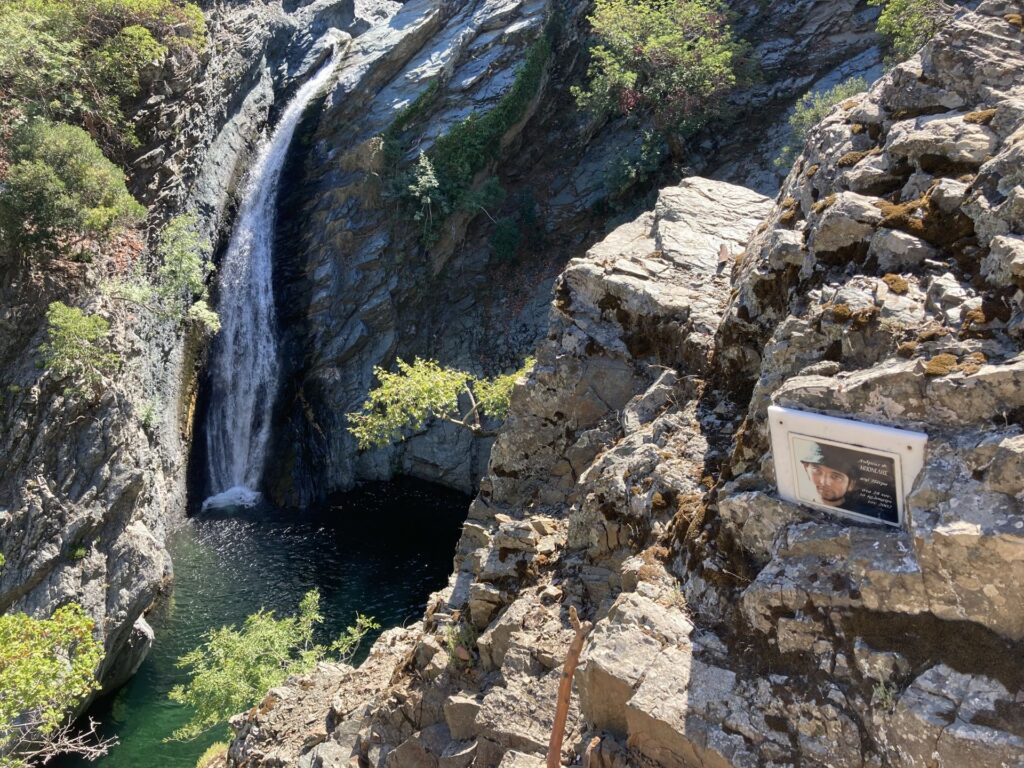

The atmosphere in the valley of Fonias is heady, but its light is like walking into an emerald. Perhaps this is how the river kills: it appears soft, but it is sharp. What does Fonias kill? Perhaps the part of me that would ever consider living in a city again after being plunged into such uncurated nature. The river that comes from the mountain spreads between islets of ferns, tree trunks, and stranded rocks, and I follow the path some two hundred meters before it leads directly into the water. A moment of hesitation, and I take off my shoes and continue barefoot, picking up the way again as it skirts the valley’s edge, past the plane trees to boulders, to a roar and a view of a great pool, or vathra, with a thundering waterfall just out of sight. This is just the first of many pools, which are said to become increasingly spectacular the higher one climbs.

I keep expecting the killing to begin. Will it be when I get undressed and enter the water, as I am sucked into a whirlpool? Or now, as I swim around the bend, to see the spectacle of the mountain’s water barreling down? Or will it happen with the next nervous return swim, to see that waterfall just one more time, to be drawn into its power, the thrilling proximity?

Because what keeps me swimming back and forth in this vathra to the dangerous waterfall is the exhilaration, like a flirtation. Yes—with each return—I feel foolhardy, but also brave, before the crush of the mountain pool.

Breathless, I dry off by the side, telling myself that there was nothing to be afraid of. Obviously, I have been warned off Samothraki so often that I approach everything with puffed-up fatalism. Fear is, after all, just something in the head. And so, I throw my clothes back on jollily and continue up the hillside but find that it is steeper than I expected.

I remember the warning of paths that go up but don’t come down. Have I now taken the wrong fork? The trail—far above the rush of the still-audible waterfall—has opened to a view of the sea and tree canopy, and suddenly ended. If I move to the right, there is a steep descent. To the left, I find a cliff. Wait—has the mountain contracted around me, to pen me in? When I look down, there are no familiar markers, no obvious trail, which is odd because I thought there had been one going up. No, I cannot find my way back.

I am lost, which is embarrassing because I am used to alpine landscapes; I grew up on trails in the Rockies. But there is something capricious and slippery about where I am now. I feel like a trick has been played on me. I inch backwards towards the sound of the waterfall, testing my feet against the rocks, which keep scattering pieces over a precipice. The sound of the waterfall grows closer, more intense, and I exhale when I overlook its roaring flood.

The killer’s waters chase gravity over the slopes of Fenghari. I sense something under the surface of this mountain: some beast that could tear open the landscape. I am an insect walking across its back and it will swat me if I am too heavy. I almost feel the heartbeat from underground.

Leaning against a stone boulder above the view to the vortex of the chasm and the pool, I look up, all slicked with sweat, to stare directly at a small plaque, a color photograph screwed into the stone.

It is a memorial to a young man—in his twenties, with thick eyebrows and almond eyes under a soft sunhat. The text is in Greek, so I understand it badly, but I know he died at this place, slipping off into the pool below or diving recklessly.

I realize I cannot take another step. Nowhere I tread is safe. The way up is too steep, and the return path remains invisible. At that moment, reading the warning, I find myself falling to my knees. And it is only when I am low to the ground that I see a way down—not a path I could have taken on foot, as I ignobly take a

deep breath. After all, as Herodotus said, “the tall trees are struck by lightning.” So, I slide on my ass all the way to the bottom.

THE HAPPIEST

The port town, Kamariotissa, is a jumble of new buildings and an ugly church. I buy more apricots and Total yogurt as I wait for the boat. In the parking lot, kids somehow have an airsoft gun and are shooting glass bottles. Their older brothers and fathers sit in shades, before Nescafé frappés, in the cafés, egging them on. The children disperse as soon as the people carrier arrives, and I watch, licking the plastic leaf inside the yogurt container. A woman in uniform gets off first, and the refugees follow her in a queue until a man in uniform disembarks and the white door closes.

As we wait for the boat to arrive, I look over my shoulder, wanting to catch the refugees’ eyes. I notice they are not downcast—there is something bright and upright in their demeanor—and they reply readily. I have understood from a glance that they know they will not be sent back; they have made it. They are the survivors.

Once we are all on the boat, and the rusty gangway pulls up behind us, and the vessel veers from the coast, I approach their circle. We are on the upstairs deck in the open, and I wonder if the accompanying police officer will mind. But he is absorbed in his cigarette. After all, where could his prisoners go? On all sides is the sea.

With a couple years of very bad Arabic under my belt, I ask where they are from. They all look at me, I think very surprised, and somehow the language comes out well for a change, and a young woman replies in the most educated classical voice I have heard for a long time: we are from Aleppo. And I remember the only time I have been to that city, before the war, when an old man took me by the arm, because we had been in the same queue buying bread, and taken me home to offer me tea.

We exchange ceremonial greetings. I’m conscious again of the presence of the police, that the passengers have been forced to sit in a circle, that I am intervening from outside. But I wonder if it makes a difference in some way to have someone speak to them in their native language, even if all I can do is ask where they are from and how they are and talk about the weather or how far away Syria is or tell them as I leave, Forsa saida.

Forsa saida: that wish of farewell to people you don’t know well, which also wishes them good fortune. It literally means “a happy chance,” or a “happy accident.” I feel that all my months of learning Arabic, with which I have done so little, have been worth it, just so I can tell them—as a stranger, as they depart to a strange continent—Forsa saida. And the elegant woman replies, with that beautiful set response: Ana al as-aad. I am the happiest.

One of the young men outstretches his hand with a cigarette, which I refuse. For a moment, I expect him to return it to a plastic bag to keep it dry. But he does not, and we exchange more greetings—Maasalama, Alhamdilileh—and I am not sure what to say, so I put my hand to my heart, as they do so in reply, wishing good fortune.

The exchange somehow makes me teary, which I do not want them to see, so I move quickly away to the starboard side, where I can watch the island of accidents retreat. As its mountain rains down clouds, I wonder—if I had only climbed up a little farther—what I would have seen. ■

Subscribe to Read More