I agree to a reading with the ambient sound artist Ceremonial Abyss, without knowing what I am getting into. What am I getting into? I want to say he creates atmospheric soundscapes using a synth and a cassette deck in the background as I read poems, but that is the wrong articulation. I am not figure; he is not ground. Lisa Robertson writes, “Noise is a confusion of figure and field,” [1] and before that, “Listening enmeshed me.”[2] This is more like it. Imagine this: The stage is a sauna; C. Abyss is heat; my poem the rush of cool air when someone enters or exits. I catch a gust of my own voice. I give up on any attempt to control the temperature.

What would it mean to pursue a craft of noise? A common definition of noise is “unwanted sound.” Noise, then, attaches to desire, albeit its inverse. In contrast, the physicist does not differentiate between noise and sound; both are vibrations moving through a medium. Noise’s noisiness is context dependent. My music may be noise to you. Or, if I play music at a certain volume, it becomes noise. Noise denotes intensity. A lack of deference for what is respectable.

Another definition of noise from Jacques Attali: “A noise is a resonance that interferes with the audition of a message in the process of emission . . . in a more general way: noise is the term for a signal that interferes with the reception of a message by the receiver, even if the interfering signal itself has a meaning for the receiver.”[3] No longer exclusively a sonic term, Attali’s noise—the interfering signal—reaches all of our senses across the variety of media that appeal to them. Techniques that manipulate the visual field to disturb legibility could likewise be said to produce visual noise. Here, noise is not the opposite of meaning, but an excess of it.

Considering the common definition of “unwanted sound” along with Attali’s definition of “an interfering signal,” we might think of noise as opposed to craft—or rather that craft works to eliminate noise. The well-crafted poem crystallizes a poetic message, works to cut away any excess and reveal a beautiful note (care taken not to produce the unwanted or discordant sound). Coleridge defined poetry as “the best words in the best order.”[4] Noise makes words difficult to distinguish, disturbs our notion of which word is which, and therefore disallows any judgment of which is best, or even which comes first; it destroys the hierarchy and sequencing Coleridge puts at the center of poetry’s craft.

But is poetry’s signal ever without static? Interference (I hope) is a multiplicity that poetry delights in. William Morris is often quoted as saying “there is no art without resistance in the material.” And if resistance makes the art? If, as poets, our “material” is language, then “resistance” in that material would be noise as Attali has defined it—“the resonance that interferes”—a word’s subtext, its haunting, its splintering. The complication of sense and sensation makes new tracks of thought possible. The interfering signal carries its own significance.

I listen to the sound of my neighbors’ TV through the wall, a news anchor drone. I cannot make out the words. A pure prosody, as it is stripped of meaning, that nonetheless escapes me. I never hear them have sex. I wonder if a reproduction of a human voice travels further than the voice itself.

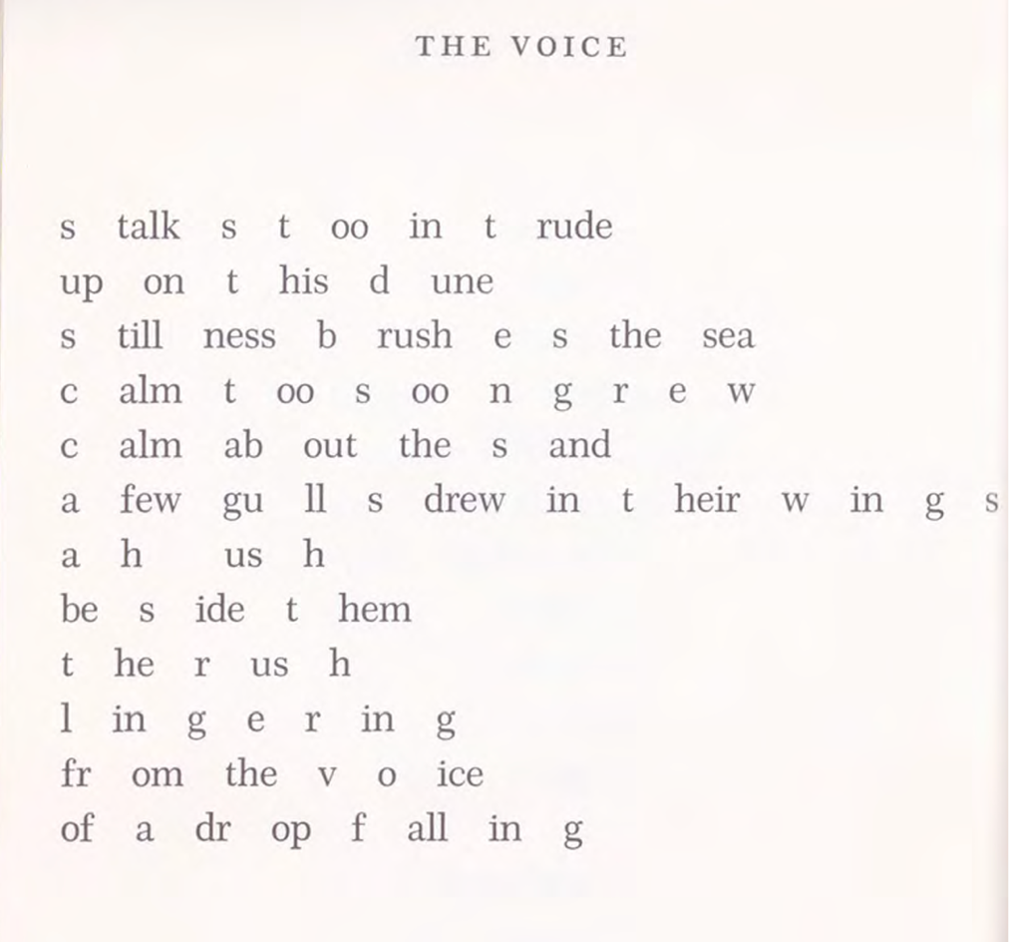

Fragmentation, paradoxically, serves up surplus. Drawing words apart reveals the words hiding within them. In N. H. Pritchard’s poem “The Voice”[5] (written in the early 1960s), words drift across the page and letters float away regardless of their syllables.

*From The Matrix by Norman H. Pritchard (Ugly Duckling Presse, Primary Information, 2021).

© The Estate of Norman H. Pritchard. Originally published by Doubleday, 1970.

Wading into the poem, we become the child just learning to read, working through by touch of ear, testing each piece for a familiar tune. The word “talk” emerges from “stalks,” “rush” from “brush,” “ice” from “voice,” and the pleasurable “oo oo” from “too soon.” These emergences do not clarify the poetic scene but embroil us in a second hovering poem: a net that flickers and obscures. Moving headlong with the “rush lingering from the voice of a drop falling,” I realize too late that I too am “all in”—awash in noise, unsure where to I’ll land. The drop—an ocean atomized—unleashes a flood.

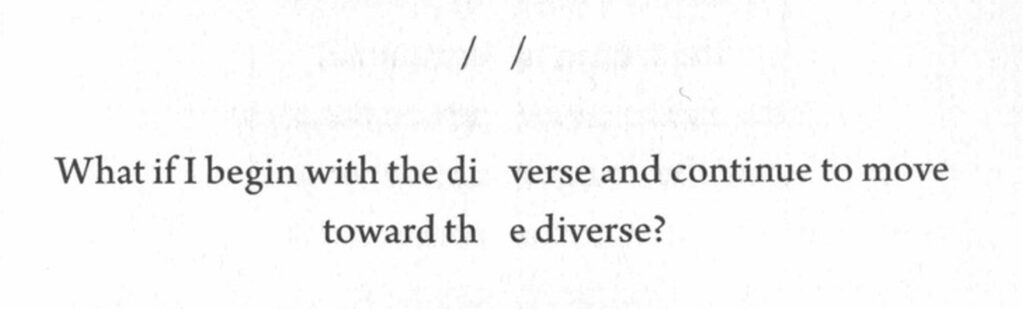

Pritchard’s poem bucks any singular or uniform voice, reclaiming poetry as a craft mired in contradiction and sensitive to multiplicity. Lisa Robertson, whose use of caesurae is resonant with Pritchard’s, asks, “What if I begin with the diverse and continue to move / toward the diverse?”[6]

*Excerpt from “The Hut” by Lisa Robertson, published in Boat (Coach House Books, 2025). Used with permission of the publisher.

This question is about, among other things, poetics: The line breaks open “diverse” to reveal “verse” nested within it. Verse is known for turning, and with each turn, making multiple. An enjambed line offers me the opportunity to finish a line in my head before I round the line break to see how it resolves; the best enjambed reversals encourage me to keep my imagined line present and in tension with the real line that it becomes. I get to have my cake and eat it too. Or, as Sharon Cameron might say, I choose not choose.[7]

Over dinner a poet asks me why I’d want to “choose not choose.” I say something about speculative grief—a poetry that continues conversations with my mother after her death, entertaining a reality where she is still alive while rooting itself in the reality that she is already dead. I need the signals I have to keep crossing. Phonograph as spirograph. My mother in a moiré shroud. The “alm alm” in Pritchard’s “calm” turns plaintive.

I read a sequence in Divya Victor’s CURB where she transcribes the sounds that are not speech from a recording of a court hearing: “f A lightweight material placed or removed (to be replaced) with a quick act onto wood or wood-like material (behind witness).”[8] I slide a pencil along a desk to bring the poem into my body. Click. Scrape. Click. Scrape. I have always been profligate in my love for the details that clutter a scene, no matter how grave.

I am proliferating signals. My definitions of noise becoming noisy: shifting, untrackable. I push on. John Cage, the experimental composer, defines noises in his 1949 “Lecture on Nothing” as “sounds that had not been in-tellectualized—the ear could hear them directly and didn’t have to go through any abstraction about them.”[9] Cage is pro-noise; as he says, “I fought for noises. I liked being on the side of the underdog.” Cage is drawn to unfamiliar sounds because their lack of conceptual baggage allows him to experience them with the body (the ear could hear them directly) rather than being filtered through the mind. This definition makes it hard to imagine noise in poetry: Words always have a conceptual tether. But even Cage acknowledges that familiar, intellectualized sounds can be remade into noises.

Paradoxically, the further Cage went into noise—as he filled his compositions with sirens, mechanical rackets, the sound of a wire skittering across a record—the more traditionally “musical” sounds were remade, estranged, and reinvigorated. Music became noisy: “I begin to hear the old sounds as though they are not worn out. Obviously, they are not worn out. They are just as audible as the new sounds. Thinking had worn them out. And if one stops thinking about them, suddenly they are fresh and new.”[10]

Trying to upend my learned rhythms I practice scanning Charlie Brown’s teacher’s voice on the page—Wah wah wah Wah wah Wah. I am disappointed to find it more or less iambic (plus one or two trochaic inversions). In the video, it puts Peppermint Patty to sleep. We like to rise and fall along a wave, even if we’re being scolded.

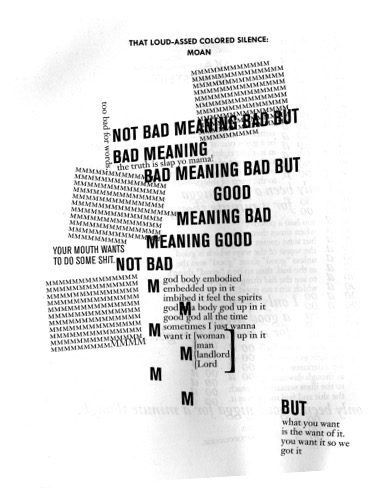

Noise disrupts our habits of perception. If Cage cuts through the “worn-out” intellectualization of sounds embracing the un-musical, poet Douglas Kearney’s poetic collages “recalibrate legibility” by performing “a kind of typographic shimmy.”[11] Kearney’s poem “That Loud-Assed Colored Silence: Moan”[12] is noisy in multiple ways. Like other poems in the series, this poem varies its font size and style, makes use of onomatopoeia and repetition, and layers text, arranging it vertically, diagonally. The result? A composition filled with visual noise.

*This poem was originally published in buck studies (Fence Books, 2016). Reprinted with permission.

The subject of the poem—the moan—is itself a sound that doesn’t rise to the threshold of language (“too bad for words”). The “M” of the moan at once escapes stable definition and motivates the poem’s sequence of sonic association—“god body embodied / embedded up in it / imbibed it feel the spirits . . .” (emphasis mine). An errant “M” obscures the lineated verse; an oversized bracket brings woman, man, landlord, and Lord into one jumbled entity. The typefaces jostle. The pieces are intimate with each other, crowded, “up in it”—no piece has enough space. This is erotic, painful. The desire behind the poem (“YOUR MOUTH WANTS TO DO SOME SHIT”) pushes the text into contact.

The Ms perform an enduring, moaning note: changing in volume, stopping at times for breath, extending beyond the square that strives to bind them. With this modulation also comes the awareness that despite its subtlety, the page cannot disambiguate pleasure and pain: Both would both be transcribed as “MMMM.” To make “sense” of the poem, the reader would have to reach for a performing body, but there is no body available to test our reading.

In his lectures, Kearney meditates on the way that he, a Black poet creating experimental work, is called upon to perform and so becomes a spectacle that makes his art legible, often to largely white audiences. Kearney resists this call to performance by trying to create poems that are impossible to read aloud: He subverts this legibility through visual noise. The poems are so noisy they become, paradoxically, silent. He writes: “In my work, I’ve meant to mess with this marvel; being a Black poet bid to sing. To hush, without voicing ‘Hush.’ To forestall a death varietal by way of a silence. Which is to say, I’ve tried to compose poems I cannot read aloud. To re-rig a visual poetics into legit, loud-assed colored silences.”[13]

I am struck by this “I” here, which is italicized in the original. To whom does it point? Is this a disavowal of lyric singularity? Could a “we” read these poems aloud? I imagine this poem performed by a choir. This multiplicity would not be harmonious; it would be disorienting, uncomfortable, discordant. It would be noisy.

My students and I sit in a circle on a carpeted floor under fluorescent lights thinking of a train’s sound. We are attempting one of Pauline Oliveros’s sonic meditations: “Think of some familiar sound. Listen to it mentally. Try to find a metaphor for this sound. What are the real and imaginary possible contexts for this sound?”[14] I close my eyes. I picture an arrow piercing a black velvet sky and then pulling it into the shape of a windsock. My students hold their own trains in mind and the room bristles like a crossroads even though we’re still. The noise is virtual. “[H]ow do you feel about it?”

Why would we want to invite noise into our poetry? Kearney’s poems might answer that noise’s “recalibration of legibility” helpfully disrupts the racialized dynamics of performance. Or perhaps that noise renders the intimacy between experiences of pleasure and pain. My own poems respond to contradictory impulses that we are too often encouraged to suppress. Some people want a poem to discipline experience. This has its appeals to be sure. Poetry can be a comfort; it can exert order. But I most often write poems from grief and desire—two entropic ways to be in the world—so entropic they expel me from the world and into poetry. Not every poem is an elegy; not every poem is a love poem; but many of mine are. Both. If we can’t help but admit these noisy conditions into our writing, into our art, how are we playing with them? Engaging them? Caring for them?

Embracing noise demands giving up control (a difficult, vital demand). I let in the thing I was trying not to say. There is something beyond our craft in noise; this is its appeal. It is a wilderness open to all. By noticing noise, we practice opening ourselves to it, feeling for the seams where language is vulnerable to its own interference.

I look in a mirror and I repeat my mother’s name out loud until it loses its edges, smudging into itself. Kit Kelly Kit Kelly Kit Kelly. Ick Ely. Ickily. Lucky. Lick Lelly. Kitten belly. Kill. Kick and yell. Kelly Kelly. A lullaby pressed through a sieve. I watch my mouth. I am named after her.

[1] Lisa Robertson, “Disquiet,” in Nilling: Prose Essays on Noise, Pornography, the Codex, Melancholy, Lucretius, Folds, Cities and Related Aporias, Second edition, Department Of Critical Thought, no. 6 (Toronto: BookThug, 2012), 63.

[2] Robertson, 59.

[3] Jacques Attali, Noise: The Political Economy of Music, trans. Brian Massumi, Theory and History of Literature (1985; repr., Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2009), 27.

[4] Susan Ratcliffe, ed., “Poetry,” in Oxford Essential Quotations (Oxford University Press, 2016), https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/acref-9780191826719.

[5] Norman H. Pritchard, The Matrix: Poems, 1960–1970 ([Brooklyn, NY]: Primary Information, 2021), 30.

[6] Lisa Robertson, Boat (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2022), 49.

[7] Sharon Cameron, Choosing Not Choosing: Dickinson’s Fascicles (Chicago [Ill.]: the University of Chicago press, 1992).

[8] Divya Victor, CURB (New York: Nightboat Books, 2021), 120. In June 2010, Divyendu Sinha was assaulted in Old Bridge, New Jersey, fell into a coma, and then died. These transcribed sequences document the recorded testimony of his widow, Alka Sinha, at the sentencing of the men who were responsible for his death.

[9] John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (1961; repr., Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan UP, 2011), 116.

[10] Cage, 117.

[11] Douglas Kearney, Optic Subwoof, Bagley Wright Lecture Series (Seattle, Washington: Wave Books, 2022), 12.

[12] Douglas Kearney, Buck Studies (Albany, NY: Fence Books, 2016), 30.

[13] Kearney, Optic Subwoof, 7.

[14] Pauline Oliveros, Sonic Meditations, American Music (Smith Publications, 1971), 31.

Kelly Hoffer is a poet and book artist. Her debut collection of poetry, UNDERSHORE (2023), was selected by Diana Khoi Nguyen as the winner of the Lightscatter Press Prize. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Gulf Coast, TAGVVERK, American Chordata, Denver Quarterly, Mississippi Review, Prelude, and Second Factory among others. Her scholarly essays and reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in Jacket2, Henry James Review, Cultural Critique, and Post45.

This is the inaugural essay in our “Staging Style” series. This quarterly craft series, edited by NER‘s Leslie Sainz, presents innovative writers, translators, and critics articulating the influences and impulses that have sharpened their thinking and writing minds.