Staff reader C. Rees talks with poet Richard Siken about associative landings, the fractured intimacy of address, and his forthcoming collection I Do Know Some Things, which features three poems published in NER 46.2.

C. Rees: These poems are quite different from the poems in Crush and War of the Foxes. They are often complexes—of sentence, sequences, and sense-making—which seem to build and rebuild themselves over and over again. They seem fixated with sequences and sequencing. Their prose-bodies and poetry minds teem with sentences. I kept encountering moments of composition/decomposition at the level of poem, line, sentence, phrase, image, word, thought. Your language—as well as memory and self—disassociates, dissolves, and reconstitutes, if not phrase-by-phrase, at least with a dreamy rapidity. They defy conclusions and dress in the skeletons of logic. I love this about them. How might you describe your relationship to the line and to the sentence? To sense itself? What was the process/method for writing these poems? What was different in composing these poems than your previous work?

Richard Siken: I had a stroke, was paralyzed on my right side, lost my short-term memory, and couldn’t make sentences. This was the experience of it. This is all I could do. There are few memorable lines in these poems. The poems hinge and swerve in the gaps between the sentences. It’s associative. It’s broken logic. The goal was to say a complete thought. That’s what I was going to measure my recovery against: a solid, complete paragraph. The sequencing of one word after another was excruciating. In conversation, I would trail off and get lost. A fundamental power of poetry is the friction between the unit of the line and the unit of the sentence. When you break a sentence into lines, you create simultaneous units of meaning. Meaning becomes a chord, not a single note. But I couldn’t break the line anymore. Everything was so broken, I didn’t want to break an additional thing. So, I had a form—the paragraph—and everything would have to be poured into identical molds. I set the margins to try to contain the thoughts. I made boxes, rooms, and sat in them and moved the furniture around. The form was the same but the strategies were different. I changed the modes (lyric, narrative, meditative, rhetorical). I wrote anecdotes, theories, definitions. I used comedy and tragedy, autobiography, hypothesis. I had a short list of movie edits and tried to vary the compositions and propulsions. I lost a lot when I lost the line, so I had to find other ways to keep it surprising and multiplicitous.

CR: I had heard about your stroke and recovery some years back, and I had that in mind as I read your new work. These poems often reach a limit of thought, language, or logic, more often than not, and reading your response clarifies how you were rebuilding something in each poem through specificity, but, as you said, the repeated mold and varying modes. I kept reaching moments where communication seemed impossible (“I am trying to tell you this but you’re not listening,”) but felt by the end of each poem that you were communicating the impossible. It appeared as though these poems were lodged in impossibility—embedded in and growing from it.

“Syllogism” stands out to me among these poems for the presence of the “you.” I’ve felt lately that anaphora has a hue of frustration to it, but a fundamental yearning futurity as well. It is perhaps utopian that reaching for another within and outside of the poem carries the necessary impossibility of distance in longing or communication. I keep recalling that syllogism’s ancient Greek root (syllogizesthai) literally means “to think together.”

What does address mean to you these days? What kind of propulsion does addressing another layer into poetry?

RS: I fell down. I was taken to a hospital. I said, “I’m having a stroke.” They said, “No, you’re having a panic attack,” and they sent me home. I kept thinking, “Something is terribly wrong. I do know some things.” That’s where the title for the collection came from. I went to a second hospital the next day and they admitted me. The organizing principle for the poems was “What do I know?” For most of the poems, I am the person I’m addressing. I was trying to locate myself. A few poems mention (or imagine) an other. It is a hypothetical other, not a specific one. Basically, I was talking to myself or reconstructing memories by myself in a hospital bed. I was hard to understand and not many people tried. A syllogism lays down premises and comes to a conclusion. My premises didn’t add up, so my conclusions didn’t make sense. There were fish moving under the ice and we were running fast at a plate-glass door. They didn’t get it. I didn’t know how else to say it. I wasn’t making meaning with my words, I was just emoting. The “you” in “Syllogism” was a stand-in for everyone who was impatient or dismissive with me. Even before my stroke, I had the problem of trying to make a point and being undercut by irrelevant questions about my first proposition. It takes too long to say it right and people always interrupt you.

The direction of address is always complicated. Even with a simple poem of a speaker addressing a lover, there’s the understanding that the speaker is being overheard by a reader, an audience. “Syllogism” addresses someone who doesn’t understand the speaker, but the author has faith that the reader (who is overhearing the poem) is leaning in, listening very closely, trying to understand. I love the start of this poem. The speaker is so frustrated and hostile. I allowed myself to get angry. The line “You don’t know them” basically says, “Shut up and let me tell it.” For the most part, I understand I’m being overheard and I take that for granted. Given that, I can address people inside the poems. Sometimes I really am addressing the reader. Sometimes, like here, the reader is someone who gave up on me and didn’t come visit me in the hospital. Or someone who showed up just to be ugly. It was nice to have a poem where I could tell them to go pound sand.

I would love to believe that the poems communicate the impossible. I think they communicate about the impossible—to be understood, to get the chance to be understood, to be able to build your argument and make your points when you are significantly damaged. You say these poems are lodged in impossibility. I think that’s exactly right. I think the dream of the possible is what fueled my recovery and return to language.

CR: I’m really enraptured by the places and scenes that emerge in the poems from I Do Know Some Things. They’re quite varied—the bedroom and therapist’s office of “Family Therapy”; the extended fantasy (and reality?) of “Drug Plane”; the lake-scape and woods in “Syllogism”—but they’re all so tactile. They seem to rise in fragments from a haze, then coalesce, bringing stark and tangible locations into relief, then ebb and phase shift into something else. These poems feel, in my particular reading and re-readings, like navigating disrupted or defamiliarized landscapes.

The words that make up these worlds seem imbued with a kind of life. The poem “Devonian Forest” especially teems with elemental presences (the wind, the snow, the forest, etc.) that grow sequentially more vivid and complex before fading out, giving space for a statement which pins the self in place: “I was drinking whiskey sours on the patio alone. I was drinking whiskey sours on the patio alone, I wrote. It wasn’t true. I didn’t even drink back then.” The antediluvian and the personal mingle so that, in one of my favorite moments from these poems, we get this: “I planted sunflowers under the windows for my birthday. By summer they were tall as ghosts.” As if, like in the Devonian Period, life radiates and spores in every direction, greening a world poised on extinction events and other worlds to come.

Do you recall how “Devonian Forest” emerged? How are the landscapes you evoke and how you evoke them, different from those that compose your previous collection, War of the Foxes?

RS: The Devonian Period was marked by the first significant evolutionary radiation of life on land. It was the era of the first forests. It seemed like a good analogy for the beginning of a story. Each choice in a story, each advance in evolution, makes one thing actual and erases all other possibilities. I wanted to jump from the Devonian to 1991 in five sentences. I needed strong images to make the giant leaps. The poem also admits that I am changing the details of the poem. I promised I would tell the truth in this book, and I do, for the most part. I point out every place where I am lying, inventing, or making a metaphor. I deal with the problem of lying in “Ventriloquist” also. I say, “I promised I would tell the truth—what’s the point of rebuilding yourself with contaminated parts?—so I told the truth.” The poem goes on to explore the ramifications of throwing your voice, of misdirection, of the performative self.

CR: It makes so much sense that these poems are rooted in your asking yourself “What do I know?” Perhaps that’s part of the tactility or tangibility that I get from your poems. The worlds within them feel at once sturdy and fractured. What is your current relationship to the world of things? Of beings, words, minds, pasts, theories, and confusion? Do you think that there is an animate quality to poetry?

RS: William Carlos Williams wrote, “No ideas but in things.” It was a central tenet of his poetic philosophy, emphasizing the importance of image and observation. I struggled with the idea. I wanted to talk about the ineffable. I wanted to show it. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t do it without landmarks, without objects. The idea has to be manifested in the image. The image has to stand in for the premises of the argument. The image is where imagination originates. Every noun is a nail that fixes the meaning to the landscape. You have to make a place tangible before you mess with it. You can’t have a transformation if the first place isn’t sturdy and located with particulars. We talk about associative leaps in poetry. We don’t talk about associative landings. You have to stick the landing. Leaping from one place to another is exciting. Leaping into the air and then trying to leap again from mid-air isn’t a successful strategy. It makes things abstract and unfollowable. It’s sometimes satisfying if you want to drift around in language. That has to be your intended project, though. If you want to be followable, you have to land on solid ground.

Life radiates and animates. Poetry does, too. In “Ventriloquist,” I say “Let’s put on a show. I’ll throw my voice and populate the landscape.” I was making a nod to War of the Foxes, where I personify and animate everything. The moon speaks, numbers speak, the landscapes speak. Even the fishsticks ruminate. I wanted so badly to invent things again, but it wasn’t in the service of the project. The landscapes in War of the Foxes are landscape paintings. The action takes place inside the paintings. There’s only one poem in I Do Know Some Things where I allow myself to indulge in sheer fabrication. In “Cloud Factory,” I let myself invent: “I was a beautiful day, I was yellow next to pink. I was a brush fire, a telephone. I was, I am. The mayor gave me a sash and a gift certificate for a complimentary dinner. He was very proud.” I also say, emphatically, “Imagination—image is the coal that fuels its little engines. Shovel coal. Call it love, call it a day’s work.” Whatever I write next will be filled with lying, misdirection, fabrication, and invention. Craft restrictions help focus a project and promote cohesion but I’m ready for different restrictions.

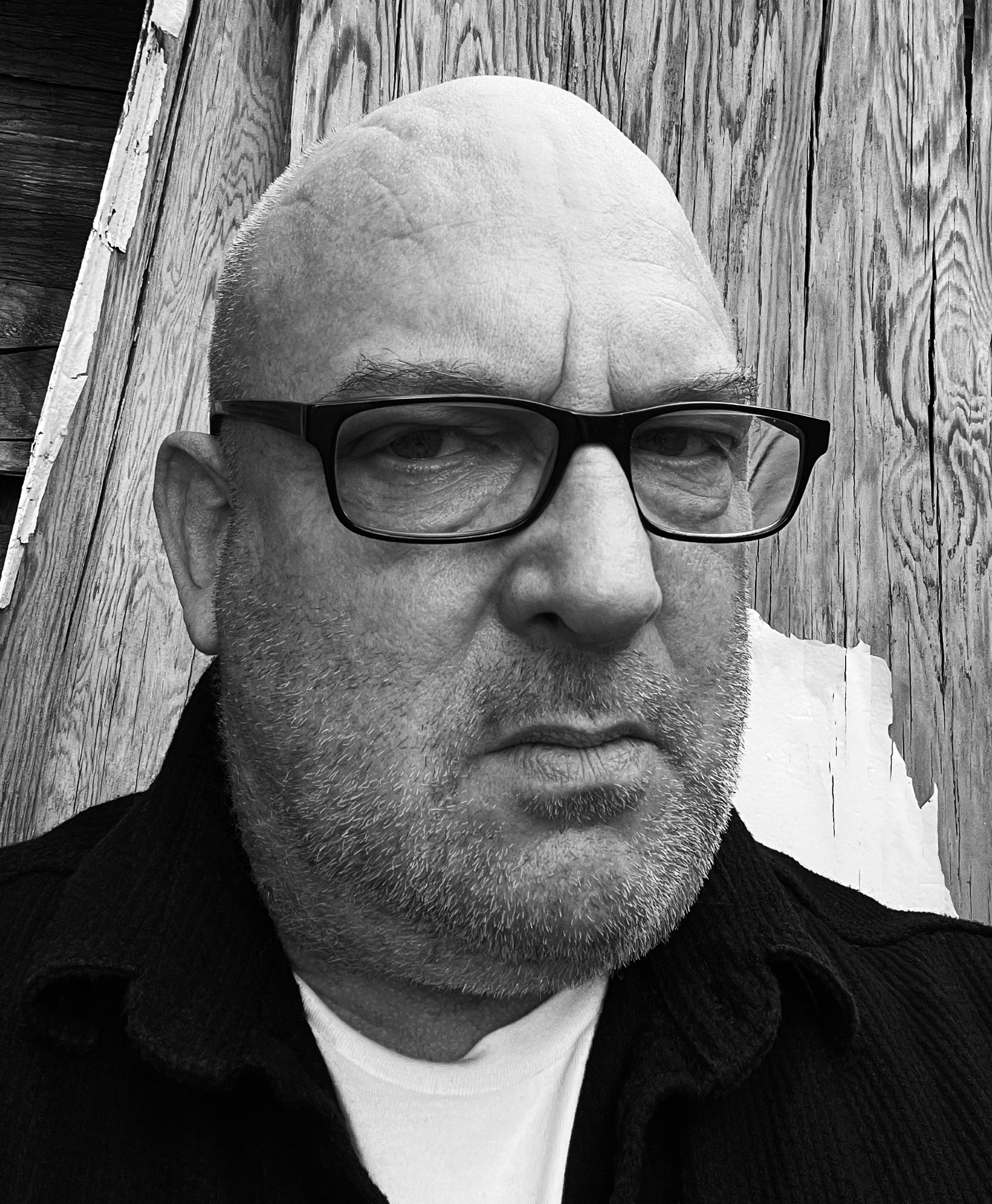

Richard Siken is a poet and painter. His book Crush won the 2004 Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize (selected by Louise Glück), a Lambda Literary Award, and a Thom Gunn Award, and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His other books include War of the Foxes (Copper Canyon Press, 2015) and I Do Know Some Things, which is forthcoming from Copper Canyon Press in August 2025. Siken is a recipient of fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. He lives in Tucson, Arizona.

C. Rees (they/him) is a queer Pennsylvania-born poet, writer, and New Writers Project alumnus living in Austin, TX. Their work has appeared in Apocalypse Confidential, Bat City Review, Shore Poetry, Territory, the Action Books Blog, the Fairy Tale Review, the Bellingham Review, and elsewhere. Their writing excavates the intersections between trauma and disrupted landscapes, toxic masculinity and queerness, violence’s contamination, memory, and complicity.