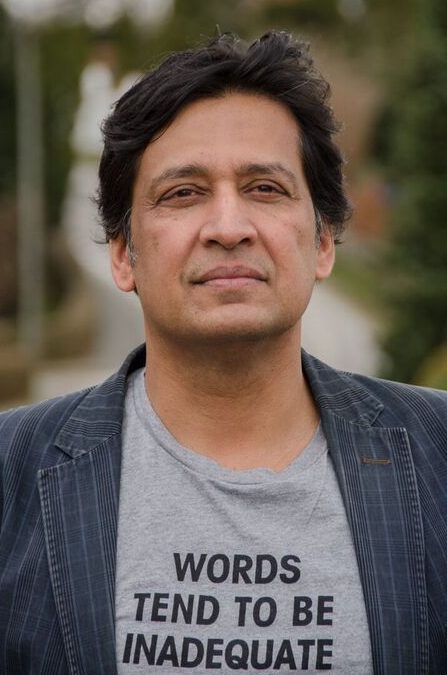

NER staff reader Meera Vijayann talks with contributor Tabish Khair about exploring language gaps, the ethics of writing the past, and the evolving dynamics of generational privilege in his essay “Birbuhoti” from NER 45.2.

Meera Vijayann: So much of your essay is a meditation on words and emotions that one can’t quite place firmly in the English language: birbuhoti, sondha. What inspired you to focus on these gaps between languages? Why does it matter to you?

Tabish Khair: One of the things I stress in my new book, which is half-study and half-manifesto, Literature Against Fundamentalism (scheduled to be published by Oxford University Press soon), is that literature necessarily works with words but also with the realization that words are never sufficient. Hence, it also works with what do not count as words in other disciplines: noise, silence, gaps, contradiction, ambiguity, etc. In this process, as a writer of literature, and as a writer who grew up between languages, the gaps between languages is vital and inescapable for me. But bear in mind that there is always a gap within the same language when, for instance, one talks of one’s experience of loss and calls it “grief.” That is why “grief” as a word is not sufficient for and in literature. It is necessary, but the writer of literature needs to do more (or less) to convey what “grief” means to her or him in a particular context. And then, of course, there is always the gap, which we struggle to overcome but do not ever manage to erase, between the writer and the reader. In short, it matters deeply to me: it is the very essence of being a writer to me.

MV: Tell me about your relationship with your father. Throughout the piece, you try to make sense of his physical and emotional violence. Yet you also say “I do not know if I am doing him justice.” Do you feel a sense of responsibility towards his memory? Most writers struggle to write about family—

TK: I feel a sense of responsibility towards the past: not homage, or admiration, far from it, but responsibility, because the past is vulnerable to the present. In that sense, it is our temporal other, and I feel a sense of responsibility towards the face of the other, that face of vulnerability, the face that is both threat and possibility, the face that, as Emmanuel Levinas puts it, calls my self into ethical being with the address: Thou shalt not kill! This is more so in the case of one’s parents, for you are formed by and against them. One can never do them full justice. They are like another age. You can never really know them. You need to relate to them, maybe even judge them, in order to know who you are. And yet, you cannot fully judge them, just as one age cannot judge another age, not fairly. The conditions, the pressures, the thoughts, the standards, everything was different. But the struggle to relate critically, if not to judge, is absolutely necessary—both for their sake and for your own sake.

MV: You talk about the class and caste dynamics of land ownership in India and explore how it played a role in shaping the dreams of your father and grandfather. They are determined to build houses and hold onto them. It was central to their identity. But it isn’t so for you. How easy or hard was it to examine this generational divide? Did you learn anything new about yourself?

TK: I cannot take too much credit for this. Very early on, I realized that if I wished to be what I wanted to be—a writer—I had to relinquish some comfortable privileges. Getting tied to property was one of them. I realized this in secondary or high school. But of course, when you are born into property, you also have the option of taking personal risks. I never borrowed money from my parents, and earned my own way from the time I got my first job as a reporter for The Times of India in Delhi. I wanted to prove to myself—and assure them—that I could manage. Even when I moved to Denmark, I did odd jobs and survived until I finished my PhD and got a regular job. And yet, I was safe in the realization that my parents and siblings had property, and I did not have to provide for them. That is a huge privilege! It gave me the space to be a writer: very few have that kind of space in the middle classes, and no one has it in the working classes.

MV: Memoir is often difficult to draft because memory is fluid. What was your process in writing this essay?

TK: Yes. The essay you read is part of about a dozen essays that I am working on: two complete and placed (one is due out in Harvard Review soon) and the rest ongoing. Three or four years ago, I started thinking of writing a memoir as a novel-like book. I could see my sixtieth year drawing close, and I thought now is the time—and then my (Danish) kids said they would want to know more about their family in India. But after struggling for a year or more, I gave up on it. I realized that a flowing A-Z narrative was not something I could achieve, or wanted to do. Memory did not flow into the form of a novel for me. It was muddy here and transparent there; it flowed like a brook here and collected into a pool there. Hence, I decided to focus on themes and episodes and write them as a series of overlapping essays. Then I could get going.

MV: What have you been reading lately?

TK: I teach for a living, so semester months are usually full of re-readings of what we have to teach. The syllabus. I seldom teach from notes, unless it is a text I dislike and cannot re-read. I prefer re-reading any novel, poem or play that I admire. I feel it improves my teaching. But this means that it is only in the vacation months that I read new stuff. The vacation month starts on 1st July here. Just reached it! Recently, I have read two novels: Neel Mukherjee’s Choice and Earl Lovelace’s Is Just a Movie. Both are writers I admire, so it is a good prelude to the summer reading.

Meera Vijayann, a nonfiction reader for NER, is an essayist and writer based in Seattle, Washington. She is currently working on her debut novel.

Tabish Khair is an Indian writer based in Aarhus, Denmark. His most recent books include Namaste Trump and Other Stories (Interlink, 2023). He has recently completed a book on reading literature as literature—arguing for its crucial role in thinking, and as an antidote to fundamentalism—which will be published by Oxford University Press in 2024.

Photo of Tabish Khair courtesy of Christopher Thomsen